The day was very warm, sultry even, and full of the heavy anticipation of what was to come.

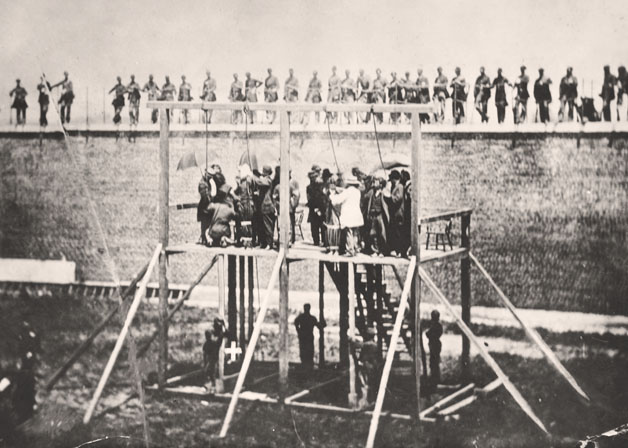

The gallows were ready; the “hangmen” were at the ready, tensely waiting for the call of the drop to be given. It was July 7, 1865. Four conspirators in the assassination of President Lincoln sentenced to hang were to meet their fate.

It was a day burned into the memory of those who witnessed it. For Civil War veteran William Coxshall, it was an especially harrowing experience. He had to be the “hangman” for the only woman sentenced to hang by the federal government, Mary Elizabeth Surratt, described as a “comely widow of forty five, whose home was a rendezvous for the conspirators.”

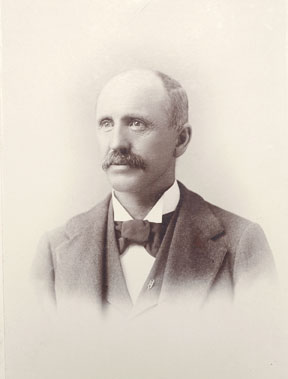

Coxshall, who after the war had a butcher shop on Spring Street in Beaver Dam, was known as a quiet, efficient man, a man of few words – reticent really. He was a tall, slim man with a large moustache and quite unlike other butchers who talked up the customers and the prices, round and rosy-cheeked and willing to throw in some liver for the cat with your order. This was Harlowe Hoyt’s assessment of Coxshall, who as a boy had to stop at the butcher shop each night and get the meat for supper. Hoyt, the grandson of Beaver Dam pioneer Dr. Ezra Hoyt, founder of the Concert Hall on Front Street, always had a fascination with the unlikely butcher, who after all did not even have all his fingers.

It would be years later that Hoyt would learn the full story of Coxshall’s missing forefinger on his left hand.

Besides having a keen interest in theatre, Harlowe Randall Hoyt became an accomplished writer and reporter. While a reporter for the Milwaukee Free Press, Hoyt secured an interview with Coxshall and learned his story was astounding, filled with all the heartbreak that came with the Civil War. Perhaps Hoyt could finally understand the unusual silence of the man, as he went through the events of his service career, culminating in participation in the execution of the Lincoln conspirators.

He told Hoyt in some detail about the incidents of the execution event when he hanged Mrs. Surratt and Lewis Payne on that hot day in July 1865. Coxshall was 22 at the time. He left the farm in East Troy to enlist in 1861. He was in service for nine months when he was discharged for a disability. He returned to the farm and was working outside when a friend passing by encouraged Coxshall to re-enlist. It was March 1864. “Wait ‘til I get my coat,” Coxshall replied. They went to town and enlisted in Company K, Thirty Seventh Volunteer Wisconsin Infantry. His friend was shot in skirmishing near Petersburg; he took a bullet in the head. Coxshall’s finger was blown away. It was crudely amputated, gangrene set in, and he was sent to Company F of the Veteran Reserve Corp at Washington after a brief furlough. There he mingled with veterans from Wisconsin, Michigan, Illinois and Indiana mostly. Members of the Invalid Corp were placed on duty at the United States Arsenal. From 100 to 120 men reported each morning and were given their orders. The work was monotonous and anything for a change was welcomed.

The Federal Commission working toward the findings of guilt and punishment for the Lincoln assassination conspiracy had made its determinations. On July 5, 1865, President Johnson confirmed sentence.

John Wilkes Booth had paid for his crime at Garrett’s farm and eight persons were convicted of complicity in the crimes. Dr. Samuel Mudd, Michael O’Laughlin, Samuel Arnold and Edmund Spangler were sentenced to the Dry Tortugas. Mary Elizabeth Surratt, Lewis Payne, George Atzerodt and David Herold were sentenced to hang. Mrs. Surratt had kept a boarding house where the conspirators gathered. Though there was a certain faction who felt she was not guilty and her punishment was unjust. Payne had attempted to assassinate Secretary of State William Seward, though Seward survived the attempt. Herold accompanied Booth on his flight from Washington after shooting Lincoln, and Azterodt was told to kill Vice-president Andrew Johnson, but backed down at the last hour.

On July 6, the Invalid Corp reported for duty at the Arsenal Prison. “We were ignorant of the findings of the Commission,” Coxshall told Hoyt. “Only the officers and those actually engaged in erecting the scaffold knew the details.” On that day Colonel Christian Rath, the man in charge of the prisoners, came in where we were assembled. He announced, “I want four able-bodied men to volunteer for special duty.” The men did not wait to hear what the special duty was. They were just anxious for a break in the monotony to which they had become so accustomed. Plenty of the men stepped forward. Rath looked them over and went down the line. He stopped before the man next to Coxshall, looking him over critically. “Where’s your cartridge belt?” he asked. “I got doctor’s permission to leave it off,” the soldier replied. “I’ve been sick.” “I don’t want you,” Rath said. Then he looked at Coxshall. “What ails you?” he asked. Coxshall held up his hand to show the missing finger. “Anything else?” he asked. “Not a thing,” Coxshall answered. “All right,” Rath said, “you’re elected.” He continued looking over the men and picked the likely ones. Following Rath into the yard of the Arsenal, they had their first hint of what their “special duty” might entail. The gallows were standing ready for the execution.

Their first order of business was the clean up of the debris and litter about the place. Coxshall and D.F. Shoupe were to knock out the posts beneath one of the drops, and G.F. Taylor and F.B. Haslett were to handle the other one. There had to be rehearsal in the prison yard. Coxshall called it “one of the grimmest things he has ever known.” Four 140 pound shells were attached to the hanging ropes with chains. For two hours the four soldiers were drilled in dropping these exactly as though the prisoners were there. The four graves were dug.

We reported early on the day of the execution July 7,1865. It was nearly 100 degrees. The event was to take place at 2:00 p.m. The first floor anterooms of the prison started to fill up with officers who watched the proceedings. There were newspaper reporters gathering. Three or four of Davy Herold’s sisters had spent the night with him. Davy seemed no more than a boy. Mrs. Surratt’s daughter had attempted to plead for her mother but was stopped on the way. She was trying to get an order to stop the execution. George Atzerodt had been visited by a woman with whom he lived. Only lawyers and a minister had been with Lewis Payne. “All this gossip helped to pass the time while we sweated under the boiling sun,” Coxshall explained.

About 11:30 a.m., Colonel Rath wanted to give the gallows drops a final tryout. “One worked all right but mine and Mr. Shoupe’s stuck,” Coxshall said. “So a carpenter was called to saw off a bit. It then worked perfectly, but we weren’t confident it would all happen as it should.”

Four chairs were placed on the scaffold and all was ready. A little before 1:00 p.m. those in charge of the prisoners, General Winfield Scott Hancroft and General John Hantraft, brought the prisoners forth. Mrs. Surratt was brought out first and nearly fainted at the sight of the gallows. She would have fallen had they not supported her. Herold was next. He appeared very frightened and trembled and shook, seeming on the verge of fainting. Atzerodt was next and then Payne. With the exception of Payne, they all seemed on the verge of collapse. Payne seemed unaffected, though they had to pass by the graves to reach the gallows steps. Hantraft read the warrants and findings, the minister spoke at length. For Coxshall the strain of it all was getting progressively worse. “I was overcome with the heat, the waiting and keeping hold on the post; I was very nauseated and vomited,” Coxshall recalled.

Mrs. Surratt had her long black dress secured to her to facilitate the drop. They tied the bands quite tight and she complained, “It hurts.” These were her final words and the matter of fact reply to her was, “It won’t hurt long.”

With three claps of the hands, Colonel Rath gave the signal.

“On the third clap,” Coxshall said, “Shoupe and I swung with all our might. Mrs. Surratt shot down and died instantly. Payne, a strong brute, died hard. It was enough to see these two, he affirmed, without looking at the others. We were told they died quickly.”

Twenty minutes later Major Porter, the presiding surgeon, pronounced the four dead. Ten minutes after that the detail cut down the bodies and buried them. Bottles containing their names were placed in each coffin.

Coxshall went on, ”We went back to camp thankful it was all over. A fight was narrowly averted on our return by some other soldiers calling us ‘hangmen.’ Had we known what it was we were asked to do as ‘special duty,’ none of us would have stepped forward. But once entered upon the task, there was no withdrawing. We were soldiers and such things were a part of a soldier’s duty during the fearful days that surrounded the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln.”

Coxshall gave up the butcher shop eventually, perhaps not wanting to be so much in the public eye, and became a successful stock dealer.

He is laid to rest in Oakwood Cemetery.