McKinstry’s Interview with Ric Fiegel

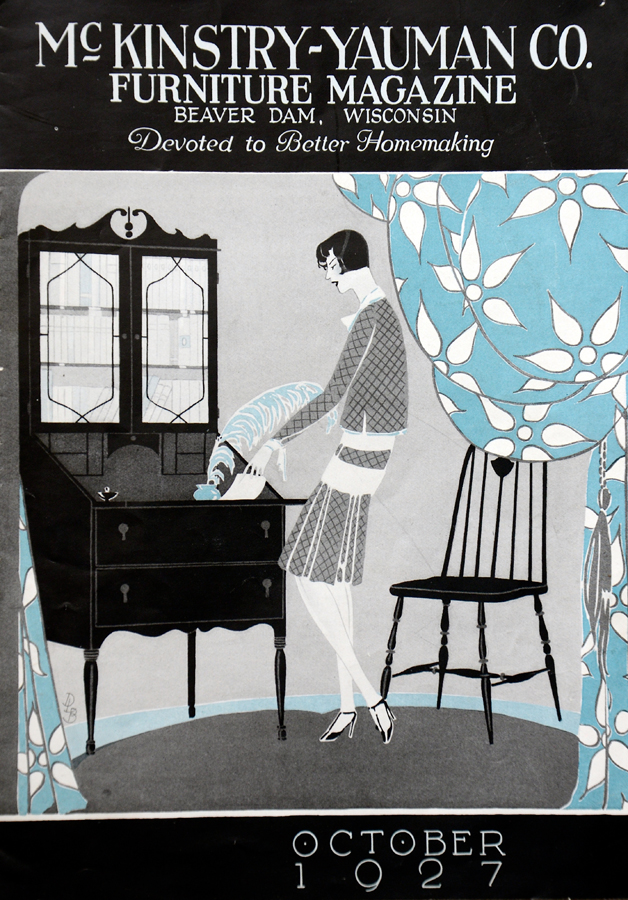

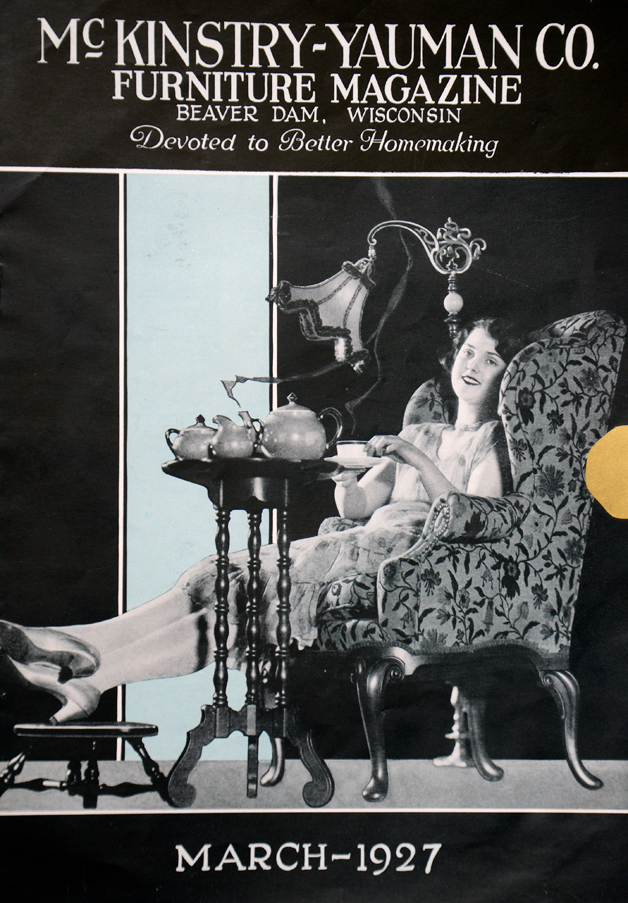

I was standing at McKinstry’s Home Furnishings sales counter, eagerly fingering my debit card as the saleswoman retrieved my newly matted and framed picture. A collection of old McKinstry magazine covers dated in the 1920s caught my eye above the counter. I was astonished and romanced by the idea that the store was so old having no idea the story was even more interesting.

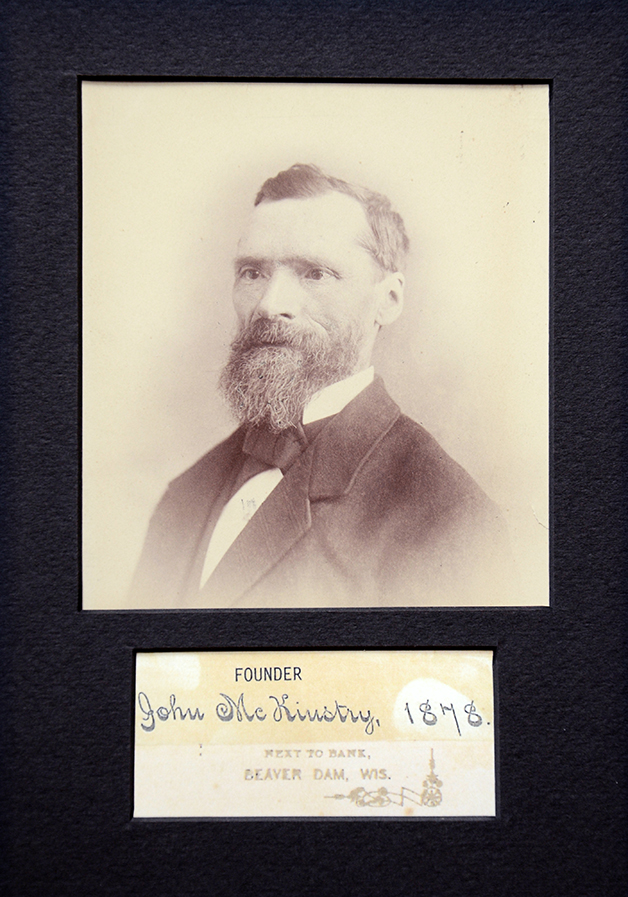

Searching through the musty photos and newspaper clippings at Beaver Dam’s historical museum in search of the past, I met a man named Jerry Kamps. I would later see him in a newspaper clipping from 1978, when he lead a mural project on the side of the McKinstry warehouse, consigned by the owner. I have memories of the chipped and peeling images I saw there every day as a child. At the time it had seemed as relevant as its brick canvas. Now painted over, the mural’s abstract images told a story that had started 120 years before the first brush stroke, when a stout Scotsman named John McKinstry first stepped onto a small town called Grubville. It was 1855. Wisconsin was only eight years old at the time, and with immigrants making up a third of the state’s population, the sight of a young foreigner and his wife would not have been unusual. What may have drawn a few post-colonial glances was the man’s stature as McKinstry was a solidly built 5 foot 2.

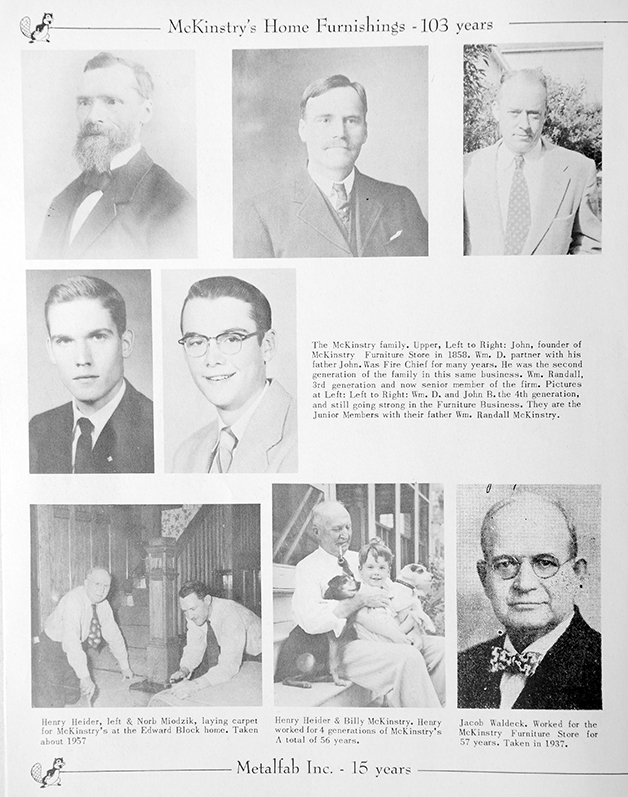

Born in Scotland, John McKinstry was among the wave of Scottish people who fled the tyranny of starvation with nothing but the hope of survival and a knack for it; McKinstry’s grandson would later describe his grandfather as “a terror for hard work.” Equipped with a trade, the cabinetmaker was soon carving a living. One of the very first pieces of furniture he made was a workbench, now retired to a life of holding potted plants in the basement of McKinstry’s Home Furnishings. The thick wooden surface has thousands of nicks and marks; it is nearly impenetrable, a testament to its original owner. The very first nick in the door-long bench could have come from his first sales push: bow back chairs. McKinstry would trudge down the frozen roads in winter with a pile of his chairs strung across his broad back. His clientele were both settlers and Native Americans, often trading goods for goods.

Three years later, he bought a modest building located across from where The Rogers Hotel now stands. Soon he was selling padded chairs stuffed with marsh grass and other luxurious pieces. His business opened along with several other standard operations in what had become Beaver Dam.

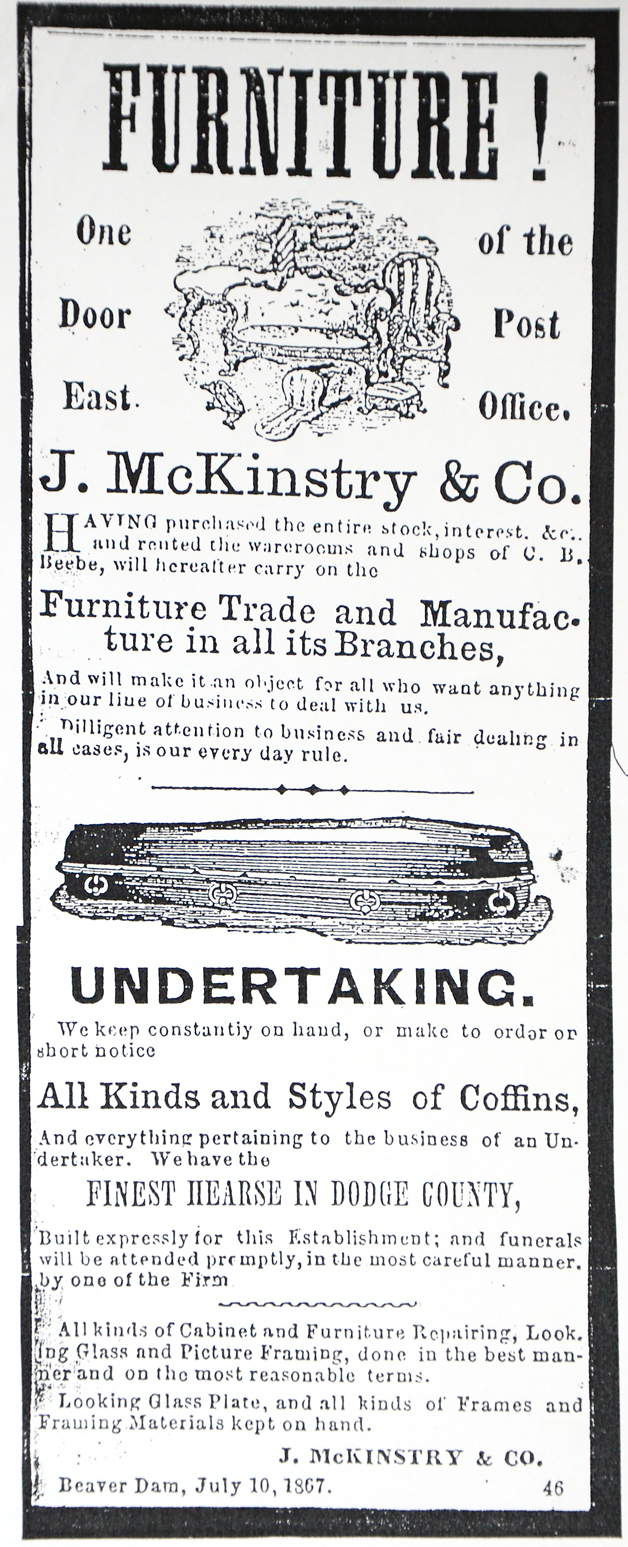

Taking on similar industries was necessary in a place with limited tradesmen, and making furniture included the construction of coffins, which lead the craftsmen to also prepare what lay inside of them. McKinstry’s store seconded as an “undertaking parlor.” By 1867 “J. McKinstry & Co.” had boomed. They bought out their competitor and McKinstry’s first known advertisement touted the “finest hearse in Dodge County” pulled, of course, by horses. McKinstry would drive the wagon he owned with the coffin he made that contained the corpse he had prepared. Once he had delivered his cargo, he would unpack a small collapsible pump organ to provide somber music for the occasion. (I know it was somber because it still plays.) Viewings began to migrate from people’s homes into funeral parlors, and adjusting to the times, John McKinstry would empty a few rooms of furniture to accommodate the grievers, who would file into a narrow space at the far end of the building. This meant one less trip for McKinstry, who embalmed his former clients in the store’s basement, pulling up the coffins in a self-service elevator still in use today.

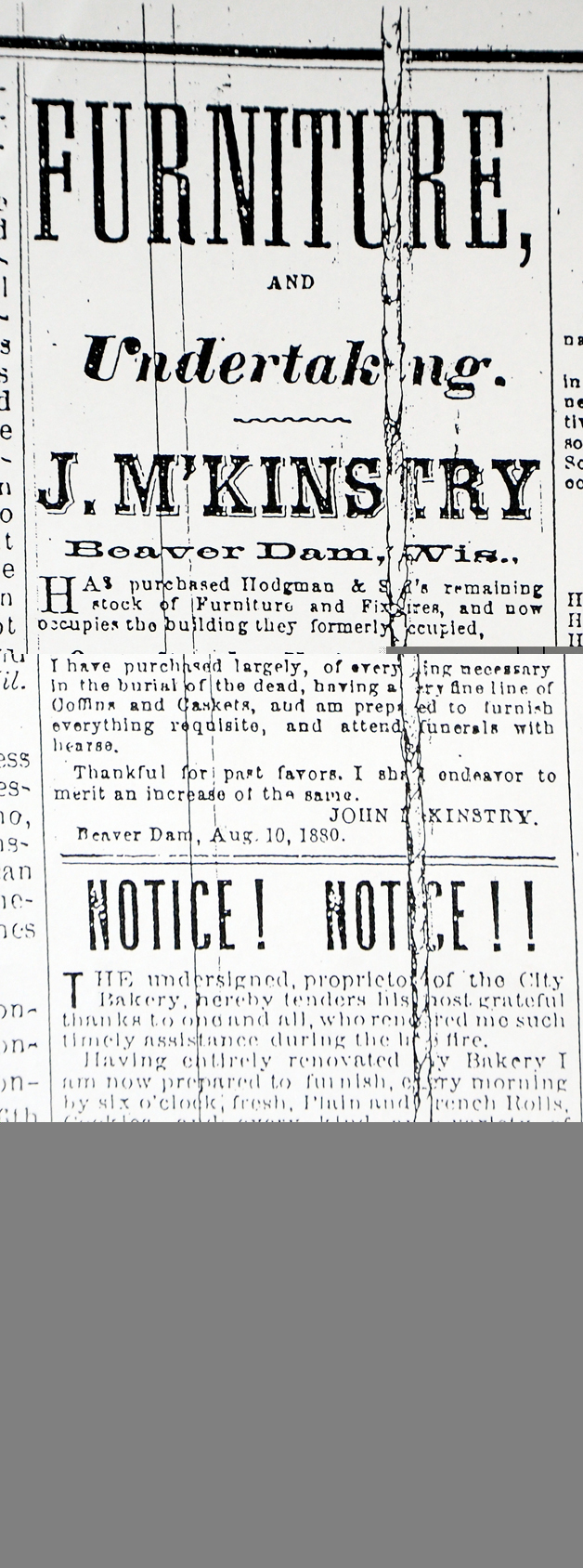

The fire that took his original store also claimed a nearby bakery, but the small city banded together to save its tradesmen! The bakery owner placed a notice in the newspaper to announce his reopening and to “tender his most grateful thanks to one and all who rendered me such timely assistance during the fire.” John McKinstry responded to the town’s aid: “Thankful for past favors I shall endeavor to merit an increase of the same.” By 1880 the store name was erected at 131 Front Street, and McKinstry’s never forgot their promise.

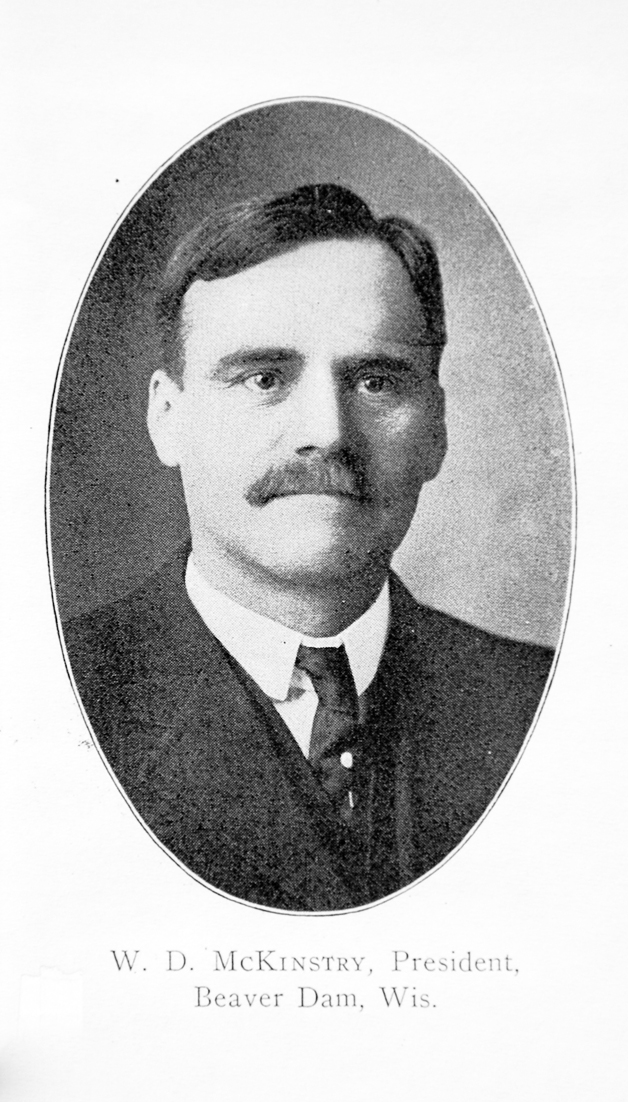

To honor partnership with his son William, John McKinstry renamed the business “J. McKinstry and Son.” Four years later, William (W.D.) McKinstry was married the day after Christmas in 1882. (Needless to say, their house was properly furnished.)

By 1890 Beaver Dam was described as “a typical small successful city” with “the hardships of its frontier days left behind.” McKinstry’s could not keep up with demand, and they began to buy furniture from outside manufacturers. The tradesmen were now becoming businessmen. True to his nature, John McKinstry worked right up until his passing. W.D. inherited his father’s work ethic and eventually his sons Irwin and Randall would join him.

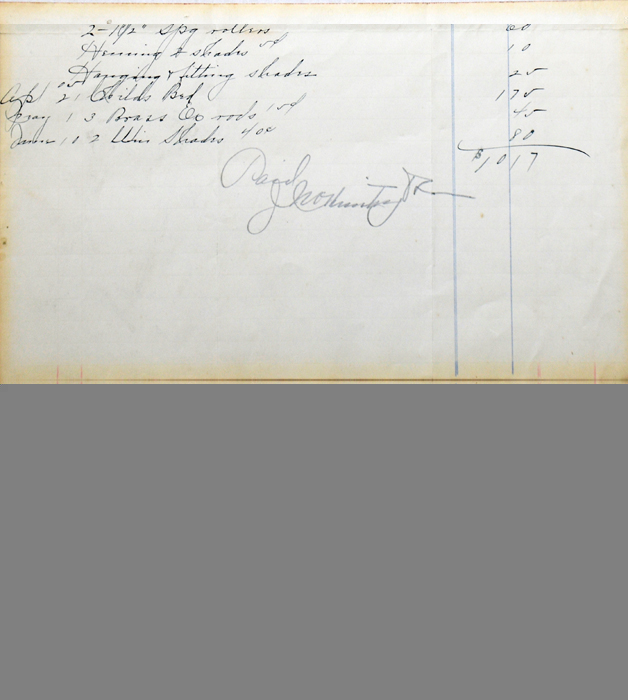

McKinstry’s dedication to the community continued. When a customer could not pay off his bill in 1915, W.D. accepted two out of six installments in the form of a sack of potatoes. And in the 1930s, a woman was hit so hard from the Great Depression she paid off her debt bringing eggs in only when she could afford it.

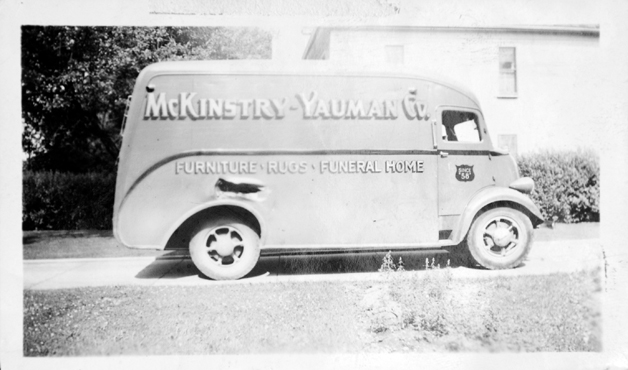

The affluent Charles Yauman entered the scene at the close of the First World War, and the store was renamed “McKinstry-Yauman Co.” Around this time McKinstry’s was one of the first businesses to acquire a motorized vehicle. It was employed as the city’s ambulance. As was common in those days, patients would find themselves being driven to the hospital in a hearse, which was the vehicle’s day job. And it would cost them nine dollars.

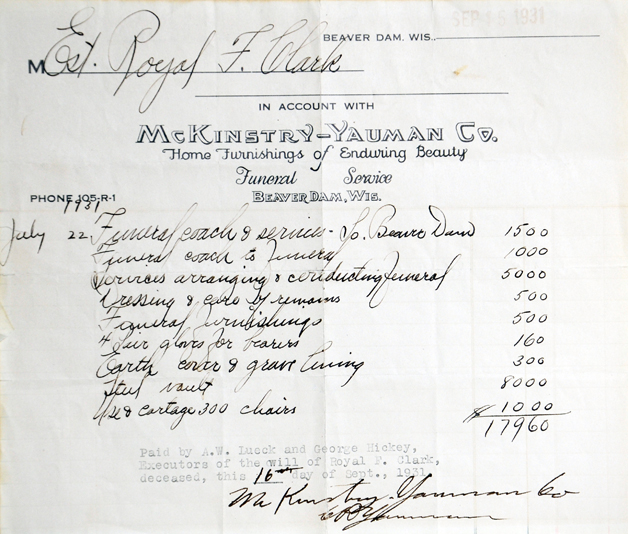

When many companies had to close, McKinstry’s survived The Great Depression in part due to their mortuary services. In 1931 a wealthy entrepreneur was buried with lavish pomp, by far the largest funeral Beaver Dam had ever seen. No expenses seemed to be spared, and all the profit went to McKinstry’s – all 179 dollars and 60 cents, with “dressing and care of remains” costing five dollars and the “use and cartage of 300 chairs” at 10. The funeral business was going so well that in 1934 W.D. McKinstry and Yauman had an additional building built some blocks away. Today that building is known as the Murray Funeral Home.

After 73 years with the business, W.D. McKinstry passed away at age 89, working within weeks before his death. A year later Randall’s brother Irwin retired to a warmer climate, and in 1953 Charles Yauman did the same. Suddenly Randall was left holding the reigns. He promptly sold the funeral home and renamed the business for the last time: “McKinstry’s Home Furnishings.”

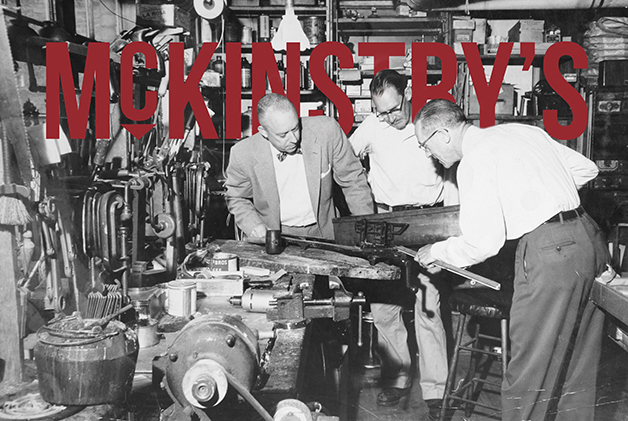

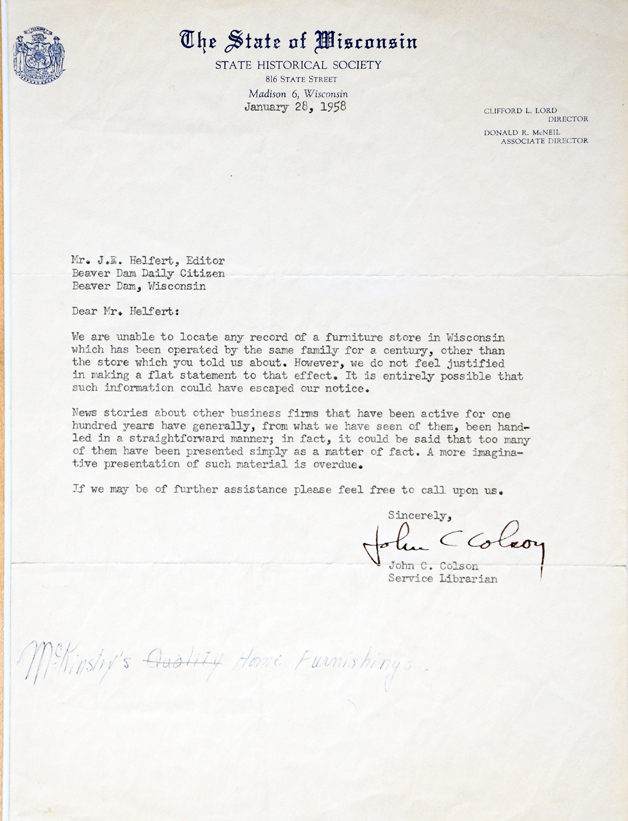

The 1950s brought another recession, but McKinstry’s survived unscathed thanks to the community giving the business “an increase of the same.” “Farmers around here are doing alright for themselves,” Randall explained to a reporter who was covering the store’s 100th anniversary. “Farmers these days are buying the best of everything and that doesn’t hurt us much.”

In 1965, John B. McKinstry began working in his father’s store, and is the present-day owner, semi-retired. Sharing a name with the man who founded one of the lasting remnants of early Beaver Dam, he is certain to be the last McKinstry in the oldest family-owned business in the state. Although not a title we may always be able to boast, the story that stretched on the side of the warehouse for 20 years showed the history of a promise. A history that is our own, that no one can paint over.