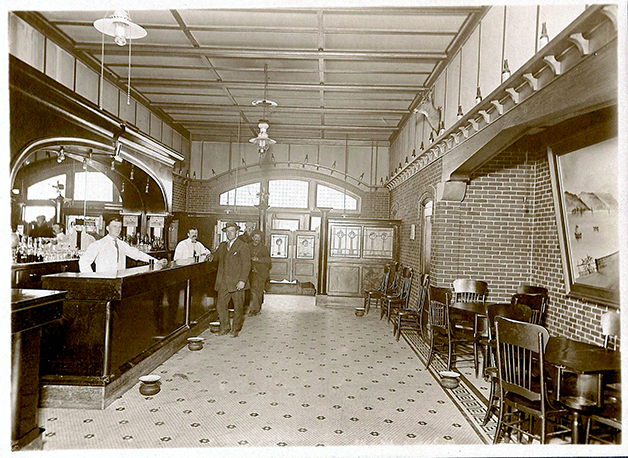

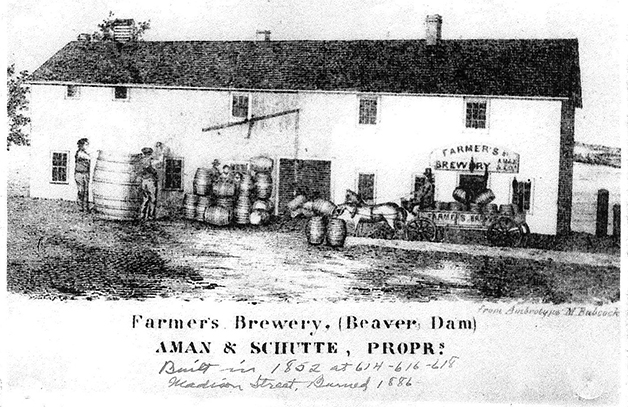

It had been half a decade of meeting in borrowed halls when the Free Masons decided it was time to start construction on their own building. In October of 1910, the cornerstone of what was 201 Front Street was laid. An impressive three-story building on the corner of Front and Spring Street, it had a small structure built adjacent to it for the J. Philip Binzel Brewing Co., a successful local brewery. As Hamlet was to Horatio, the turreted Masonic building once described as the “cornerstone of downtown Beaver Dam” overshadowed the neighboring pub at 203 Front Street that was crowned The Fountain Inn. Small even by peer standards, it possessed its own architectural uniqueness. With a wide-arched front window the building is meticulously designed and beautifully made, having held its original character for more than a century. Amidst the high quality of craftsmanship, its bar stood out with the front’s mahogany finish, its marble base and arch above the back bar with articulate design.

Snowstorms stalled construction, and the Free Masons formally dedicated the Masonic Temple in June of 1911 in a ceremony that drew a crowd of over 200 people. The Fountain Inn’s patrons, however, had been quietly dedicating the modest building tagged “the Binzel Building” daily since January, and its manager was not likely displeased with the crowd outside the door.

Herman Bork was the saloonkeeper under contract with the brewery. He was the face of the tavern, and according to the Dodge County Citizen, he carried a “good line of liquors and cigars.” Every morning he likely opened around daybreak for men who needed a mixed lift on their way to work be that in an office or a mill. Dawn sifted through the broad-arched transom window designed to reflect maximum light into the narrow interior. His saloon-keeping tasks included sweeping floors, polishing spittoons, washing glasses and filling the ice box with shaved ice, all before the lunch and supper influx of patrons. Mr. Bork would likely walk the few blocks to his house on packed dirt sidewalks in the twilight of dusk as horse-drawn buggies clanked by. He would pass a few of the 30 other saloons in the city before reaching 221 Maple Street where he lived with his wife, five children and a boarder. Life was lived in the same rhythm for nine years until the culture shock of 1920, which put Binzel Brewing Co. along with its manager out of business. ‘Buffet’ was tacked after ‘Inn,” and 13 years of prohibition would see three owners.

The official breweries were all shut down, and Beaver Dam had its share of bootleggers with gangsters from Chicago commissioning underground brewers from the region. The FBI had the national task of extracting the bootleggers. One underground brewer was found operating on what was then the property of a grade school. Another bust near a farm lead to a police chase in the middle of downtown. The sirens blared past the former tavern as the bartender served up another soft drink. In 1927 Ray Gray (known as “Roy”) had declared the business a soft drink parlor, and as he said privately to his wife’s cousin, “They never found where I hid the liquor.” Patrons could though, if they had the right connections. Disguised bottles were hid under the mahogany countertop and served with discretion. Buying and then selling the tavern during prohibition, Roy purchased it again at the end of prohibition after serving as an employee for six years and ran it until 1958.

Small wooden fishing boats would commonly dot Beaver Dam Lake in the 1930s. As a young boy Cletus Willihnganz, now in his late 80s, noticed a larger boat with heavy equipment making its way to the main island in the center of the lake from time to time. One summer’s day he and his friends climbed inside the heavy docked boat. The craft’s owner was loading materials away and gruffly told them they could play inside the boat, but not to touch any of the equipment. It was later learned that the island was being used as a brewery location, and the materials were the main ingredient, sugar. The authorities never found out.

People celebrated the end of prohibition in 1933, and Roy restored the tavern’s original name, but it was affectionately known as “Gray and Zink’s” under eventual co-ownership. There was a respectable cliental. Roy wore a crisp white shirt and black tie every day to work, and men would frequently bring their families along; the kids entertained themselves in a back booth with a soda pop. He never slacked in its maintenance, and there were not many bars that would be described as “beautiful” by the people who remember it, especially not of the restrooms as well. For 22 years Roy and his wife lived in the apartment above, with its wooden cabinets and claw foot tub, while he served behind the bar below. People in progressing fashions sat at the front bar and discussed Al Capone in the 30s, the start and end of World War II in the 40s, and the legendary Bobby Fischer. In 1958 a sixth owner took charge for six years until 1964, when a Beaver Dam man named Howard (Howie) Louden took ownership, adding his last name to the tavern’s title. The longest single ownership the bar would see, 203 Front Street was the home of Louden’s Tavern for 28 years. During that time people would open up their newspapers at the bar reading headlines that included Neil Armstrong walking on the moon or drop in for a nightcap after seeing Star Wars for the first time at the movie theater across the street. Howie was four years older than the structure itself, graduating in the same 1925 class as Arthur P. Zink, a former owner of the tavern, and actor Fred MacMurray, his friend and former band mate. Howie served drinks along with interesting and pertinent conversation, opinions and memories as his time allowed behind that 24-foot bar top until he passed away in 1992.

The Fountain Inn remained ownerless until Jay Hoeft reopened it as ‘Emotional Rescue.’ The end of Jay’s ownership of the historic tavern would be anything but an emotional rescue for the owner. In the spring of 2010, torrential rain flooded much of the Midwest, and Beaver Dam’s downtown was closed off for several days as the authorities prepared for the dam to break. It never did, but the flooding had done its damage. The city central that was built overhanging the river below the dam was condemned, and Beaver Dam citizens of the 21st century watched as their history was torn to the ground and carried away as heaps of rubble. Renamed The Fountain Tavern (shortly before) and inconspicuous for more than a century, this condemned building now stands between bleak spaces in an obvious silence that is anything but discreet. While the building is set to be demolished, the oak back bar was rescued in 2011 and survives, transplanted behind the doors of ‘The Fountain’ a downtown Madison bar and restaurant. A picture of the bar’s historic origin hangs on the wall, overlooking a new century.