By: Jason J Gullickson

Getting to Know You: Tell us a little about yourself. I was raised in Edgerton and attended public school until my sophomore year of high school when I left to be homeschooled, although I had been home- and self-taught for most of my life. I obtained a GED, spent two years at Blackhawk Technical College in Janesville and then moved to Madison to pursue work supporting desktop computer operating systems. I spent about a decade as an IT consultant, during which time I met my wife Jamie. We married, and a year later we were expecting a child. We left the city to raise our daughter in a community that fell midway between Edgerton where I was raised and Green Bay where Jamie was brought up. Since leaving Madison I have worked professionally as a programmer, systems analyst, consultant and chief engineer for a number of companies. During this time I have also learned enough carpentry to repair and improve our home in Beaver Dam, produced a number of films (short dramas and feature documentaries), designed and built a number of electronic devices (including a 3D printer), developed a number of pieces of Open Source software, provided volunteer IT consulting and software development services and learned a lot more about the liberal arts from my family and community.

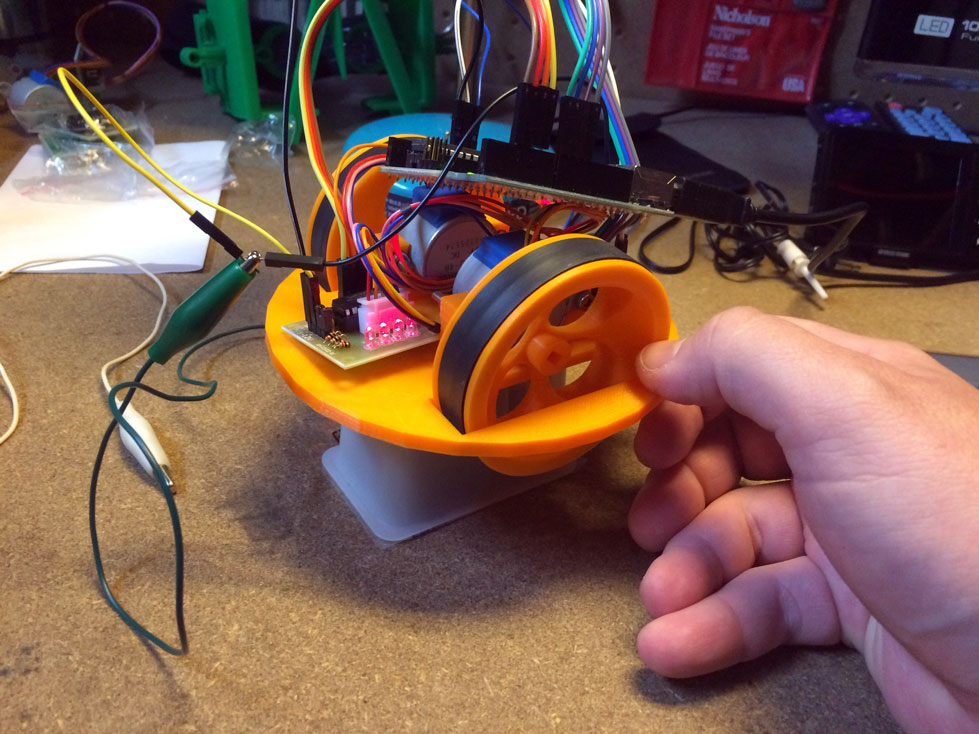

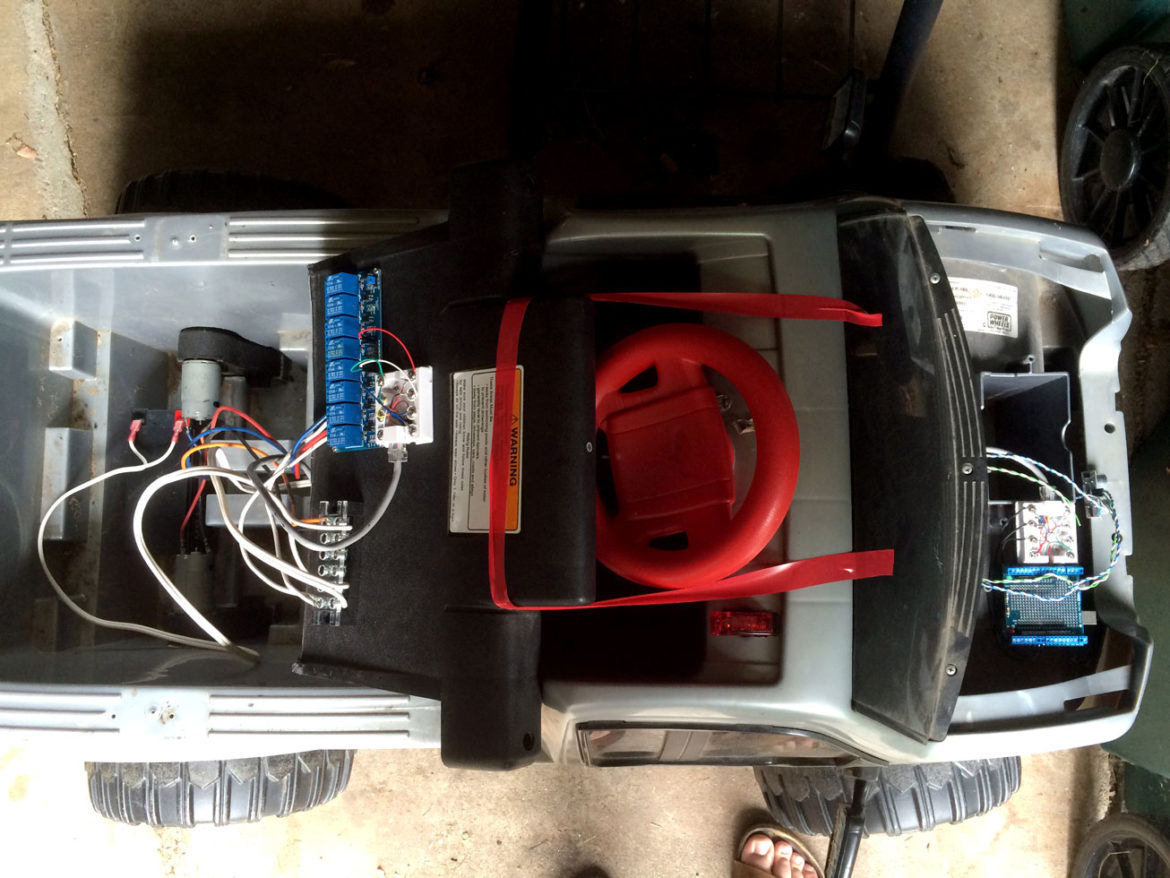

What is it that you make? The short answer is, “Anything that I want or need that doesn’t already exist or is too rare/expensive/regulated for me to acquire otherwise.” A more specific answer is software, electronics, tools, robots, movies, music, vehicles, engines, alternative energy systems, virtual reality, artificial intelligence and some carpentry/woodworking. Those are the big ones. I dabble in just about anything, and I’m always interested in picking up new skills and knowledge that can be used for fabrication.

How did you get started? I don’t remember the first things I made but I have fairly detailed notebooks that go back to middle school, and I’ve seen photos from earlier. My parents are both makers and I spent a lot of my early childhood by their side as they made and repaired things. Building toys (Erector, Lego, Tinkertoy, etc.) were my most prized possessions as a child until I received my first computer for my 8th birthday. I had been learning to program on my father’s computer, but once I had one of my own, I had the ability to create things endlessly, without being constrained by limited parts or tools, which completely absorbed me.

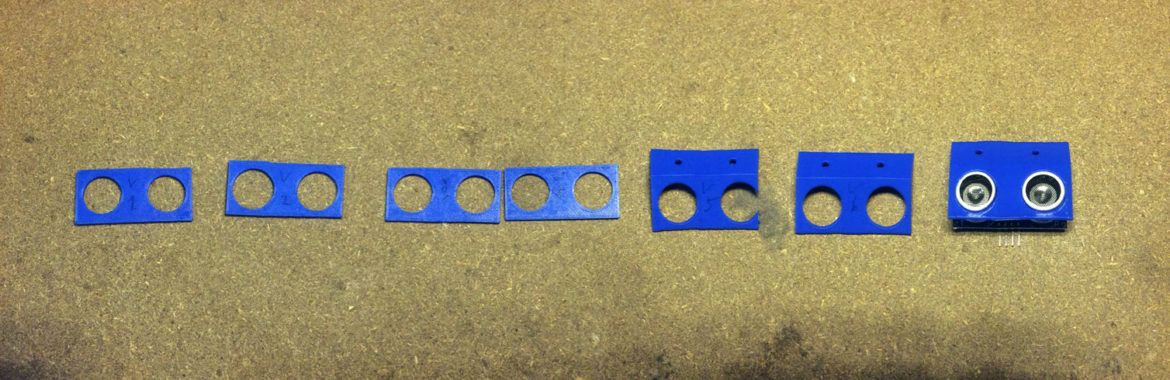

Tell us about your current projects. This is tricky because it’s rare that I consider a project “done,” so at any given time I have many, many current projects. That said, projects I’ve made progress on recently include something we call “Storyphone,” which is kind of like an audiobook for our Little Free Library, an autonomous Powerwheels truck (primarily as a test platform for general-purpose autonomous vehicle and robotics experiments), a new type of data storage device, upgrades to my 3D printer monitor software for the Pebble smartwatch, building additional 3D printers… those are some of the highlights.

Why do you do what you do? Every project has unique specific motivations, but abstractly it boils down to three reasons: 1) It makes me happy; 2) It makes others happy; 3) It has to be done to facilitate 1 or 2.

How do you work? From a process perspective I work intensely on one project at a time, but I’ve learned to quickly switch when I get stuck, so it gives the appearance that I’m working on a lot of things at once. I used to get very hung up on getting stuck, and it’s a problem because a lot of the things I like to work on involve hard problems or require skills I don’t have (or perhaps don’t exist yet). What I have learned is that when this happens, putting down the work and doing something else is the best thing to do, so I do this with conscious discipline. I’m not going to pretend like that is easy; getting close to solving a problem or making something work, only to be held back by one small detail, is very frustrating, and “doubling-down” on the work is incredibly seductive. But in almost all cases doing so only creates more problems, whereas walking away for a while almost always generates better outcomes, and doing something else (even if it’s just walking around the block) tends to result in insights you overlooked when you were focused on one problem. I call this “target fixation,” a term I learned from a motorcycle class instructor describing what happens when you try to avoid a pothole by looking at it. The motorcycle goes where you look, so if you’re looking at the pothole, you are probably going to hit it. Instead, look at the path around the pothole. This works for most problems, but I’ve found that when you’re focused entirely on the problem, you can’t see around it (like a zoomed-in camera lens); instead, walk away and let some attention fall elsewhere, and often a good solution will bubble up. I’ve been known to “park” a project this way for years (decades?). Often when you’re creating something new you have to wait not only for your knowledge and skills to improve, but for the world around you to catch up as well.

How has your craft changed over time? I think the biggest change has been in the form of “Accessibility.” The Internet has made access to the data (diagrams, spec. sheets, etc.) and the knowledge (academic papers, historical information, DIY projects, etc.) needed to pursue projects like mine almost universally available to anyone with Internet access. The hardware (computers, electronic components, tools, etc.) have also become significantly less expensive and easier to find (also due to the Internet) than they were when I was getting started, and even for most of my life. This is why I, and many other makers in my fields are very protective of the Internet and the Open Source philosophy that created much of what we think of as the Internet. Without this level of access, much of the progress we all enjoy (makers and people who don’t identify as makers alike) would not exist without the free exchange of information and ideas the Internet makes practical.

What is your goal with your craft? If there is a goal, it’s to improve the tools and pass them on so those who come across our path can go a little further. Something that is often overlooked when looking at making something vs. buying it is that there is value in making beyond the result. Making, as a means to an end, is often a dubious proposition…it’s easy to look at something like a DIY guitar amp project that costs $50 in parts alone and see it as foolish when you can buy a new, ready-to-play amp with similar specifications off the shelf. However, consider that we pay money to be entertained in our spare time. We go to the movies, we pay for cable TV, and we buy boats and cars, etc., and when you consider the money spent to entertain yourself for the 5-10 hours it takes to assemble the guitar amp, you might just break even with the kit.

Beyond the basic economics, building the guitar amp makes you smarter. It also prepares you to repair the amp should it break down. It also informs you as to how the amp works, which can in turn impact your playing. Possessing an understanding, if even an incomplete one, of how the amp works can lead to innovations in music you might not have been able to imagine without the experience of building it. This is just one example of how the simple cost comparison decision-making process overlooks deeper and more subtle value generation that making vs. buying creates.

Also, you end up with more tools if you build it, and I’ve never wished I had fewer tools.

What is your dream project? This would be a project whose only constraint is Quality. This is so very rare to find in commercial or professional work, so a project that only answers to delivering the highest quality results, without constraints of time, cost, etc., would be incredible to work on. Imagine a world inhabited by things made this way!

What is your background? What jobs have you had besides being a Maker? Most of my professional work has revolved around information technology (IT). I’ve done work ranging from tech support to network engineering, programmer to system architect. I’ve never been employed directly as a maker, but most of my professional work has benefitted the troubleshooting and fabrication skills I’ve honed working on my own projects. It’s fun to imagine what I’d be able to do if I could pursue any of my projects exclusively, without needing to be both inventor and investor. Much of my more recent interests are in creating a social and cultural environment where more people can explore such a path.

Deep & Fun Questions: What’s your strongest memory of your childhood? My earliest memory is being electrocuted, but I’m not sure if I actually remember it or if I’ve just heard the story enough that my brain has re-created a very strong imaginary version.

Describe a real-life situation that inspired you: The crisis on Apollo 13 comes to mind; the space program is filled with great stories about making things work under almost unimaginable constraints. I’ve been reading a lot lately about people hacking together personal computers during the cold war in countries where importing hardware from the west was banned, and both their drive and creativity to pursue that work under those conditions makes me think how much more we could be doing with the tools and technology we have access to today.

What is your most embarrassing moment? I used to get really embarrassed and bent out of shape for making mistakes when playing live shows with the band. It was embarrassing at the time because I felt dumb for making mistakes; it’s embarrassing looking back now because I got so worked up and the audience didn’t really care.

What memorable responses have you had to your work? My memory isn’t great, but the one that stands out recently was finding that an Open Source code I wrote years ago wound up being used as the basis for a number of projects around the world, including a custom piece of hardware designed by another maker. When I wrote the software I felt like it had a lot of potential, but at the time it was hard to find anyone else who got excited by it. Turns out this is an example of an idea that needed to wait until the world caught up, now that there is a marketing term for this sort of technology (“Internet of Things” or IoT) people have a context in which to understand the work, and I was thrilled to see something that I had kind of gave up on was now accelerating the work of others.

What food, drink, song inspires you? We love fresh local food, and cooking is one of Jamie’s many talents, so I’m very spoiled in that regard. As you’d expect, coffee is a key component to my work as well as the occasional energy drink. I do like to listen to music while I work but I prefer simple, repetitive and fast music when I’m concentrating even though I don’t like to “listen” to music like that when I’m not working. If the music is too interesting, it’s distracting, but having a beat to listen to seems to pull me along when I slow down.

What makes you angry or what do you dislike about your work? Tool failures (stripped fasteners, wrong sizes, etc.) are probably at the top of that list, the second being unable to get the right part. The latter problem is sometimes a source of inspiration so I try not to let that one get me down, but it’s easier said than done.

What superpower would you have and why? Flight, I just love flying. If not flight, I might like to have tentacles; I’m always short on hands. However that would probably make it really hard to find clothes, so they would have to be removable like Dr. Octopus or something.

Name something you love, and why. If we’re talking about things I have some favorite tools. I have a 12v Milwaukee drill/driver that is almost like an appendage to me and might be the most durable electrical device I’ve ever owned. I have a Das Keyboard Model S Ultimate that is so good that I’m designing my own laptop just so I can have a keyboard that good outside of the lab.

Name three people you’d like to be compared to. Thomas Edison, Nikola Tesla and Tony Stark (good luck reconciling that).

Where is your favorite or most inspirational place in Dodge County? Jamie and I have cultivated some of our greatest ideas over hot beverages at Black Waters Coffee, although we both find nature just as inspiring, and Ledge Park might be one of my favorite outdoor places nearby.

What is the best piece of advice you’ve been given? It’s hard not to drop a platitude in here. Conceptually the idea of “Quality,” as described in Robert Persig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, has been instrumental in understanding why I’m drawn to work that appears unimportant or impractical superficially. Also the understanding that failure is dependent on giving up has kept me going through numerous struggles. Another of my favorites, one that I use often as an analogy, came from one of my first CPR instructors. When asked by another student, “but what if we hurt them doing CPR, like breaking ribs and stuff.” The instructor replied, “Well, they’re not getting any deader.”

What wouldn’t you do without? My wife Jamie and our daughter Liberty. I wouldn’t be here without them. They are a continual source of inspiration and, in the context of this conversation, have been the greatest critics and collaborators that I’ve worked with. Everything I do is better for contact with them, and I hope I can provide even a little of that back to their projects and ideas.