The Indian Prairie burial and ceremonial site at Kletzsch Park

By: Mark D. Olsen

February 8 2019

When Increase A. Lapham, Wisconsin’s first and finest scientist, surveyed the Indian Prairie in May of 1850, we were the youngest state in the fledgling nation at exactly two years old. In 1848 the newly-formed Smithsonian Institution published the first volume in its “Contributions to Knowledge” series, “Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley”. This publication focused on indigenous earthworks in the Mississippi River Drainage. Several Wisconsin monuments were included.

Seven years later the Smithsonian Institution published Increase Lapham’s seminal work, The Antiquities of Wisconsin as surveyed and described (1855). Among the ancestral earthworks mapped by Lapham is the Indian Prairie site which is located in and near today’s Kletzsch Park. The site sits above the west bank of the Milwaukee River in the city of Glendale, Wisconsin.

Southern Wisconsin’s indigenous burial mounds belong to an underappreciated and misunderstood culture. Academics and authors of popular effigy mound texts have miscast this monumental building program and consider it something less than organized and cohesive. These conclusions were based largely on faulty precedents and too little fact-based research. This is especially so as regards to directional attributes of effigy mounds.

Based on several years of study, I will unequivocally state that there is an inherent and logical order encoded in Indian burial and ceremonial mounds. This includes conical mounds and linear mounds, both of which were also found on the Indian Prairie site.

One longstanding opinion tends to only designate people as “civilized” if they organize in hierarchical structures similar to western institutions. This type of Victorian-era thinking has been hurtful and is factually wrong. Stateless societies, like the mound builders of ancient Wisconsin, organize and build complex societies based on shared rituals, which help enforce social norms (Stanish 2017). Ceremonial sites like the Indian Prairie are evidence of this form of social organization. Ritual and religion is not always the same thing; a nuanced understanding is required.

Places like the Indian Prairie were known to family and friends who lived throughout southern Wisconsin. These are not primitive societies. The mound builders weren’t pagans either. I support through extensive research that the path to “heaven” for the effigy mound celebrants is the same one, the Milky Way, which is described by Plato and that describes the worldview of people in the Near East when the New Testament is written. The Milky Way as the Path of Souls is the core ideology encoded in conical, linear, and effigy mounds.

Foundational stories in Genesis, such as Jacob’s Ladder, also support the notion that North America’s indigenous religion shares core traits with the Babylonian and Sumerian traditions that are known to have contributed to the Old Testament. We have gotten so much, so wrong, for so long that it is hard to correct or explain everything at once but we can do better in the future. The formal religion practiced by the effigy mound celebrants includes belief in an afterlife and deep reverence for ancestors.

The Indian Prairie, like other earthwork sites, encodes and records a cohesive and logical afterlife-based religion. Most Indians, almost all of them, are not buried in mounds. Ancient burial mounds are also ceremonial monuments that can be thought of quite literally and accurately as prayers written in earth. The Indian Prairie seems undeniably linked to several effigy mound sites upstream on the Milwaukee River near present-day West Bend, Wisconsin. These sites are all within one day’s canoe ride and share similar cross-shaped mounds that are a somewhat rare subset of effigy mound. This is a sign of cultural complexity and suggests that a religious guild of some sort operates in the locality.

Indian Prairie was a shared sacred site where people gathered to trade, socialize, and celebrate. Effigy mound celebrants likely petitioned ancestors with health and resource-related prayers that were directed towards the Milky Way’s position just after dark in southern Wisconsin’s summer months. An alternate portal to this Path of Souls, the Hand-and Eye constellation, based on our Orion seems used in other-than-summer months. The three belt stars in Orion form the wrist of the hand in the sky that is part of many oral histories.

Effigy mounds and other earthworks encode a lot of information, including dates, that can be deciphered as if symbols or letters of an alphabet. Asking or expecting living descendents of the mound builders to have retained this type of ultra-specific information is both unrealistic and I think vastly unfair. It is little different than demanding that I recall and explain specific information from the Viking era in 800CE. It doesn’t make sense.

None of this means that the Indian Nations present in Wisconsin today, particularly those most-closely associated with known deep-history links to Wisconsin, the Menominee and the Ho-Chunk Nations, have forgotten their past. Quite to the contrary, this research reveals that common themes retained by Indian Nations today, such as honoring the cardinal directions, showing deep reverence for ancestors, and considering the Milky Way as the Path of Souls supports the idea of a continuous culture that extends deep into history. Some Algonquian speaking peoples know the Milky Way as the Path of Birds; this similar theme is found in northern Eurasia as well as among indigenous people in South-Central Siberia. The deep history potential of this concept is astounding.

The precise timing mechanisms that are encoded in earthworks such as at the Indian Prairie seem to me to be lost cultural knowledge. That core parts of this encoded system survive in many current-day forms is precisely what we should expect based on some anthropologic theories.

Ideology at the Indian Prairie

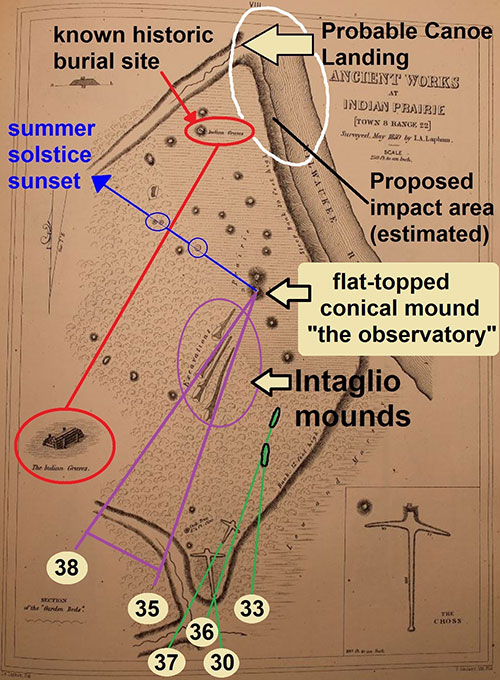

Few people even know that Milwaukee County’s Kletzsch Park was once a significant ceremonial and religious setting for American Indians. The sacred gathering site stretched for nearly one-half of one mile on the Milwaukee River’s west side. There were conical burial mounds, circular ring-shaped earthworks thirty feet in diameter, two linear mounds, two cross-shaped burial mounds, a large flat-topped “observation mound”, and four of the rarest ancestral monuments in the world. These four intaglio mounds were excavated into the earth rather than being built on top of the earth. Figure 1. Indian Prairie near dam looking south. Map data: Google Earth; adapted by author

Figure 1. Indian Prairie near dam looking south. Map data: Google Earth; adapted by author

Figure 1 shows the current dam at Kletzsch Park, the proposed construction zone with mature trees slated for removal, the approximate site of the last known Indian burial at Indian Prairie, and the open field where portions of the ultra-rare intaglio water-spirit monuments might have been buried but not destroyed by early agricultural activity.

While the intaglio prairie is not under immediate threat of development, these intaglio features are so rare they deserve consideration as part of a long term planning process. Without going into great detail, magnetic gradiometer techniques have been perfected (Dr. Jarrod Burks) in recent years to help relocate buried pit-like features such as might still exist at the Indian Prairie. It seems plausible that the agricultural-era fill deposited in the intaglio earthworks might, in consultation with Indian Nations, be considered for removal in a way that would not require either taking away or adding anything new to the theoretically buried original monuments. This area might be noted by park planners. It should remain unaltered until proper non-intrusive investigations can be carried out.

The two largest above-ground features at the Indian Prairie can also be placed with high confidence in the field with the intaglio features. One of these was the central “observation” mound that Lapham identifies in his 1855 text. This flat-topped earthwork was the viewing platform from where it seems the galactic center and Milky Way is sighted over the intaglio water-spirit mounds. This is an important location. The large flat-topped observation mound also had quite precise alignments with the aforementioned ring-like earthworks. In recent years it has become accepted that most ancient societies which undertake monumental building programs often mark the solstices. This is common. As with the intaglio water-spirit mounds, the thirty-foot-in-diameter ring-like earthworks had pits in their middles. It is possible that these too might be relocated along with the intaglio water-spirits, though less likely because of the railroad embankment.

The two cross-shaped burial mounds at the far southern end of the Indian Prairie (figure 6) have “partners” upstream near the Milwaukee River in the West Bend area. Cross-shaped mounds are a relatively rare form of effigy mound. There were two very prominent cross-shaped mounds at L.L Sweet’s “Ancient Works” site (Lapham 1855: Plate X) on a bend in the Milwaukee River nearNewburg, Wisconsin. Lizard Mound County Park (The Hagner Mound Group) sits three to four miles north of Sweet’s site. It also has two large cross-shaped mounds; they have been previously misidentified as bird mounds.

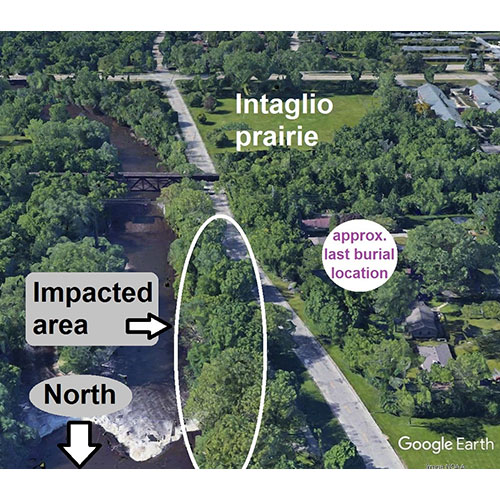

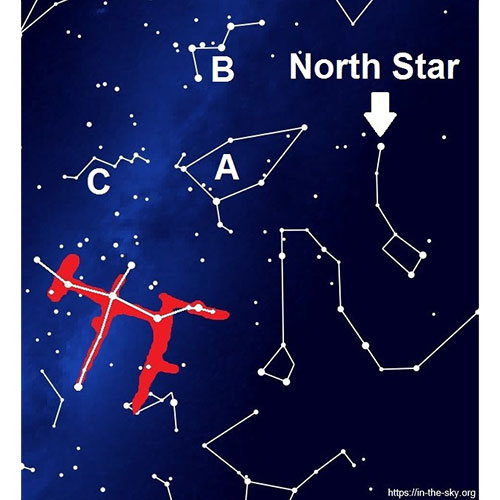

An interesting H-shaped earthwork that is Northern Cross-related was mapped by Lapham at the Horicon site (1855: Plate XXXVII). Figure 2 shows the accurately scaled outline of this complicated mound as it might be envisioned sitting in the middle of the Milky Way. As it sat on the ground near the lower end of the Horicon Marsh, the cross’s descending shaft aligned in the south-southwestern direction that coincides with the rice harvest. The stars that extend along the cross beam belong to what peoples all over the world have found to be a bridge that crosses a fiery, milky, or raging river. This too is common.

If we look at the two cross mounds at the Indian Prairie site as shown in figure 6, we find that the smaller cross points in exactly the same direction as the complex Horicon cross. The southernmost cross mound aligns just east of south along survey line no. 30 in my measurement system. This orientation is going to coincide with an earlier-in-the-year Milky Way position. Survey line no. 30 translates to a date when the galactic-center portal appears very near to the summer solstice, June 21. This fits well with the other apparent solstice alignment at the Indian Prairie where the three ring-like earthworks sit on a summer solstice sunset line as viewed from Lapham’s observatory mound. The Indian Prairie marks the summer solstice by referencing both the sun and the Milky Way.

Figure 2. Unique cross mound from the Horicon site. Map data: in-the-sky.org; adapted by author

Please take a look at the clustering of orientations in the 30 to 38 range in the Indian Prairie map (figure 6). In my study, I measured more than 750 earthworks based on a 64 segment system that I designed for a reason. I then searched for patterns, central tendencies, and only then explanations. Note the two linear mounds that align to no. 33 and no. 36; these are commonly observed orientations that in theory record calendar dates for near the beginning and the end of July. These too are reasonable timeframes in which to expect people to gather at a place like the Indian Prairie.

The four intaglio earthworks exhibit directional characteristics that focus on the south-southwestern horizon. This is a tell-tale sign that these features are associated with an early August to early September timeframe. When Increase Lapham maps the site in 1850 he tells us:

Four of the excavations lie in a southwest direction from the two larger central mounds. In approaching the former from the latter, a small trail or path is discovered, which gradually, becomes larger and deeper, until it leads into a sunken area… [Lapham 1855:18]

I think these deep intaglio-related trails might also show up with magnetic gradiometer testing if someone gives it a try. This can be part of an educational outreach as well as an extremely interesting and important research initiative.

The cross mounds in nearby Lizard Mound County Park help us determine that these types of earthworks relate to the constellation Cygnus, also known as the Northern Cross. Figure 4 shows the summer sky with an accurately mapped cross-shaped earthwork from Lizard Mound County Park outlined against the sky. Figure 3 shows the two cross-shaped mounds as they sit within the Hagner Mound Group at the neutral-territory gathering spot which is today partially preserved in Washington County’s Lizard Mound Park.

Figure 3. Cross-shaped mounds at Lizard Park. Map data: Ancient Earthworks Society Inc., Prehistoric Geometrical-Based Art Work on the Ground: Wisconsin’s Effigy Mounds 1991; adapted by author

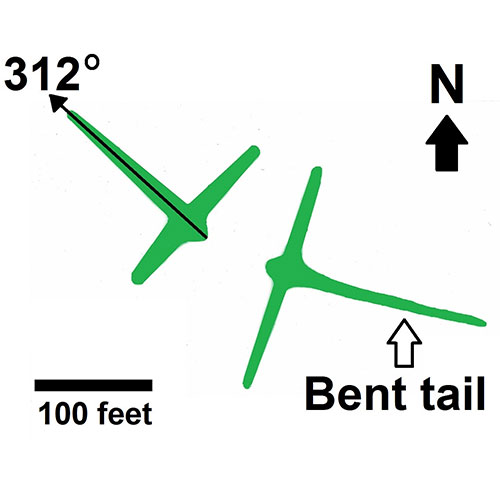

The southernmost cross mound at Lizard Mound County Park was accurately mapped by highly respected cartographer Jim Scherz and the Ancient Earthworks Society (AES) team in 1991. The AES noted that this cross mound has a hard-to-explain but obvious slight curve to its tail; this is quite evident in person. It is almost as if the cross is plucked from the sky and placed on the ground.

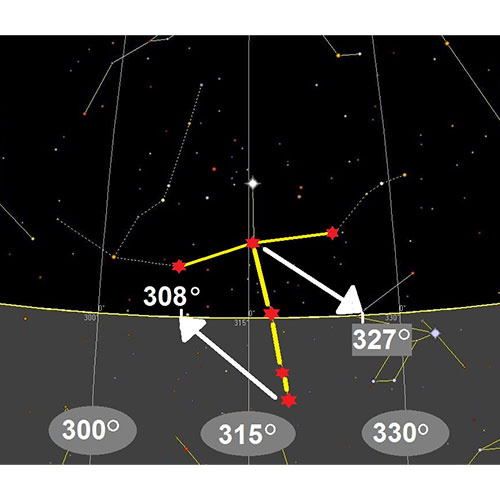

The northernmost cross in this twinned-pair has a long staff that points to a 312° azimuth.This was troubling as it is not a Path-of-Souls-allowed orientation. Eventually, I determined that this odd directional characteristic seems to relate to the Northern Cross’s set point where it drops below the northwestern horizon in the 850CE timeframe. This is shown in figure 5. Star rise and set points change slightly but steadily over time because of precession. This needs to be calculated and is helpful in dating mounds.

Figure 4. Bent-tailed cross mound outlined against summer sky. Photo and adaptation by author.

Figure 5. Northern Cross set point in 850 CE. Map data: SkyMap Pro 12; adapted by author

In summation, I wanted to show and share some of the sophistication and humanity that was recorded at these types of mound sites. The Indian Prairie was an important cultural site that is still important. I recommend that we leave what is still intact in place. Let’s honor these sacred soils.

With hopes that this essay has helped illuminate a bright era in human history, I thank you for your time and attention.

Mark D. Olsen – Report researcher and writer

Figure 6. The Indian Prairie. Map Data: The Antiquities of Wisconsin, as surveyed and described, 1855: Plate VIII; annotations and photo from 1855 first edition, by author

Click here for a PDF version of this article – The Indian Prairie Burial and Ceremonial Site at Kletzsch Park

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

< Open letter regarding construction on the Indian Prairie site PDF version >

Open letter to public officials and decision makers regarding potential construction on the Indian Prairie site

This isn’t just one of many beautiful spots in the Milwaukee County Parks system. The Indian Prairie is a known ancestral site of high importance. For thousands of years, families and friends gathered on the high banks overlooking the Milwaukee River near the proposed construction area. The two-hundred-plus-year-old oaks in construction’s path are the last living witnesses to a continuous Indian presence here that extended many millennia into our collective past. Some of these gentle giants might have even felt Increase Lapham rest on their thickening trunks as he shared an apple with his horse Billie.

For sure these oaks towered tall enough to observe and participate in the last Indian burials at this location – which were still happening when Lapham mapped the Indian Prairie. In 1850, Lapham finds a well-made, above-ground Indian grave and notes that every log and even the supporting stakes are made of the same type of wood. This helps to show the reverence that Indians had for the special nature of certain trees. Oak trees have a very strong association with effigy mound sites across the state; they are grandfathers in their own right.

When opportunities arise to prevent further destruction to ancestral lands that are in the public trust, we might consider taking actions that are sensitive to our nation’s natural heritage and history. This is one of these times. Forgiveness begins with words but it requires confirming actions to show that regret is authentic. Acceptance is never guaranteed, nor can it be demanded. Actions can show where our hearts lay; genuine remorse need not be accompanied by guilt or shame.

Are we really ready to cut and kill the last witnesses to Indian ceremonialism at this site? And then tear out the turf and bluff on which it stands? Might it not be time that we stand as one with the oak and whisper our support, perhaps even an apology for their loss too, even if in silence? Let’s let our actions speak. They can be our words.

Jim Uhrinak and Martha Bergland, we support your call for consideration of options that provide for proper fish passage through the artificial impoundment area at Kletzsch Park on the river’s east bank, to preserve the west bank’s oak bluff.

Effigy Mounds Initiative

Kurt Sampson

Mark Olsen

Interested parties can find more information on the historic Indian Prairie site in the articles, “Effigy mounds explained” and “The Indian Prairie burial and ceremonial site at Kletzsch Park” on LocaLeben magazine’s website https://www.localeben.com/

We ask that readers consider joining us in supporting Jim, Martha, and others in the Glendale community who want to see options considered that do not disturb remnants of the Indian Prairie at Kletzsch Park. If so inclined, these public officials can be contacted with your questions, support, or concerns with the current project’s proposition to remove six heritage oak trees and the associated bluff where Wisconsin’s first peoples gathered for millennia.

City of Glendale Mayor

Mr. Bryan Kennedy

414-228-1712

Milwaukee County Board Supervisor

Mr. Theodore Lipscomb Sr.

theodore.lipscomb@milwaukeecountywi.gov

414-278-4280

Milwaukee County Executive

Mr. Chris Abele

chris.abele@milwaukeecountywi.gov

414-278-4211