Publishers Note: This feature originally appeared in our May / June 2013 print edition.

Lloyd Clark

By: Lloyd Clark

We all know someone that is “a slave to fashion.” A fashion slave is a person totally consumed with ensuring that their clothes, their hairstyle, their physical appearance and even their possessions conform precisely to the current “hip” style. They religiously read GQ and Cosmopolitan magazines; have their televisions set on the E, Style and MTV channels (heaven forbid they miss a Red Carpet!); and spend more on clothes and grooming products than most of us do on our cars. I am sure you know the type.

However, did you know that fashion was once used as a weapon to keep half of the US population and other “civilized” countries, submissive and subservient to the other half? It is true. The Diors, Laurens and Versaces of the mid-1800s were less fashionistas and more female overseers, as the designs of Victorian women’s dress discouraged social interaction and encouraged domestic compliance.

The Age of Enlightenment, that great intellectual awakening that inspired our Founding Fathers to experiment with a radically new form of national government, somehow managed to bypass the women of the time. One poignant example of this is a letter from Abigail Adams to her husband John Adams, who was attending the Constitutional Convention. Mrs. Adams writes on March 31, 1776:

“I long to hear that you have declared an independency. And, by the way, in the new code of laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make, I desire you would remember the ladies and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors.

“Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the husbands.

“Remember, all men would be tyrants if they could. If particular care and attention is not paid to the ladies, we are determined to foment a rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice or representation.

“That your sex are naturally tyrannical is a truth so thoroughly established as to admit of no dispute; but such of you as wish to be happy willingly give up – the harsh tide of master for the more tender and endearing one of friend.

“Why, then, not put it out of the power of the vicious and the lawless to use us with cruelty and indignity with impunity?

“Men of sense in all ages abhor those customs which treat us only as the (servants) of your sex; regard us then as being placed by Providence under your protection, and in imitation of the Supreme Being make use of that power only for our happiness.”Unfortunately, John Adams, our Second President, did not really listen and joked in his response, “Depend upon it, we know better than to repeal our masculine systems. Although they are in full force, you know they are little more than theory. We dare not exert our power in its full latitude. We are obliged to go fair and softly, and, in practice, you know we are the subjects.

“We have only the name of masters, and rather than give up this, which would completely subject us to the despotism of the petticoat, I hope General Washington and all our brave heroes would fight.”

When they said that “all men” were created equal, they were being very specific and not only were women forgotten in the U.S. Constitution, but the ratification of state constitutions as well.

Upon ratification of the state constitution, women specifically lose the right to vote in New York in 1777; Massachusetts in 1780; New Hampshire in 1784, and in every state other than New Jersey in 1787. In New Jersey, the wording of the constitution gave the right to vote to “all free inhabitants” who met certain property-owning requirements. Women who owned property utilized this loophole to vote – until 1807, when the New Jersey legislature took the right away.

This had to be especially galling to Sybil Luddington, who on the night of April 26, 1777, rode more than 40 miles through towns in both New York and Connecticut gathering the militia and warning that the English Redcoats were attacking Danbury, Conneticut. Sybil, who was only 16 years old at the time, rode twice the distance than Paul Revere did. Not only was Sybil’s hometown renamed in her honor, she was given a Revolutionary War Veteran’s pension in later life.

At this time, and up until the 20th century, women, considered the physical and mental inferior to men, most often found themselves relegated to lives of domestic drudgery. A woman’s place was in the home, and as the Victorian era dawned, the fashion trends changed to encourage this.

Victorian fashion for women, based upon the ideal of an “hourglass” figure, began to be taken to an extreme and unhealthy degree. For most women, attaining the ideal figure necessitated the use of a most evil invention – the corset.

In Catherine Bardey’s 2001 book Lingerie – A History and Celebration Of Silks,

Satins, Laces, Linens, and Other Bare Essentials, Ms. Bardey says of the corset “…the rigid royal court formality that had been abandoned during the Revolution returned and the ideal female form was the hourglass… By the 1840’s corsets became so complicated and such a chore to put on or take off that a few women simply left them on day and night for the best part of a week. Personal sanitary standards were, needless to say, at a low point.

Ms. Bardey went onto say, “The ideal Victorian woman had a severe, wasp-like waist. The more tightly laced her corset was, the more virtuous she was thought to be. Every part of the Victorian woman was covered. The slightest peek of an ankle or glimpse of the lower part of her neck was considered to be unmentionable.”

If the corset was not bad enough, fashion called for a “billowy” look for the skirt, which entailed the use of up to 14 pounds of petticoats to give it the desired look. No gentle woman of the day would be caught dead in public in anything but this full “uniform.” It is no wonder that most women found it more expedient, and comfortable, to stay home where their daily “chores” necessitated a less restrictive outfit.

It is not hard to imagine that American women that longed for, if not equality, at least emancipation from their subservient role would realize that the restrictive clothing was representative of the restrictions that the male-dominated culture imposed upon them. Knowing American women as we do, it is not surprising to learn that they “fought back” in a way that shocked men and subservient women around the world – they wore pants.

It was really the Abolitionist movement that seems to have been the catalyst for this revolt. According to the US National Park Service website for the National Historic Park in New York, “In 1833 (Lucretia) Mott, along with Mary Ann M’Clintock and nearly 30 other female abolitionists, organized the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. She later served as a delegate from that organization to the 1840 World Anti-Slavery Convention in London. It was there that she first met Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who was attending the convention with her husband Henry, a delegate from New York. Mott and Stanton were indignant at the fact that women were excluded from participating in the convention simply because of their gender, and that indignation would result in a discussion about holding a woman’s rights convention. Stanton later recalled this conversation in the History of Woman Suffrage:

As Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton wended their way arm in arm down Great Queen Street that night, reviewing the exciting scenes of the day, they agreed to hold a woman’s rights convention on their return to America, as the men to whom they had just listened had manifested their great need of some education on that question. Thus a missionary work for the emancipation of woman…was then and there inaugurated.

Eight years later, on July 19 and 20, 1848, Mott, Stanton, Mary Ann M’Clintock, Martha Coffin Wright, and Jane Hunt acted on this idea when they organized the First Woman’s Rights Convention.

Throughout her life Mott remained active in both the abolition and women’s rights movements. She continued to speak out against slavery, and in 1866 she became the first president of the American Equal Rights Association, an organization formed to achieve equality for African Americans and women.”

With Stanton, Mott, and Susan B. Anthony as leaders, the convention approved policies calling for equality in the law as it related to women, especially in the areas of child custody, divorce and property rights. Further, they called for expanding career opportunities for women especially in medicine, education, law, and as clergy. They also made the outrageous argument that women deserved equal pay for equal work and that they should have the right to vote! The first Women’s Rights Movement since Abigail Adams had been born.

One of Stanton’s admirers was Amelia Bloomer, who published the first American newspaper strictly for women, The Lily. Bloomer began the newspaper focused mostly on temperance articles, because she found public speaking “unseemly” for women at the time; however, she felt that women could more easily relay their ideas to other women through writing, especially on the destructive influence that alcohol was having on families at the time. Bloomer proudly proclaimed that The Lily advocated for “the emancipation of women from temperance, intemperance, injustice, prejudice, and bigotry.”

In the very first edition, Bloomer wrote, “It is woman that speaks through The Lily…Intemperance is the great foe to her peace and happiness. It is that above all that has made her Home desolate and beggared her offspring… Surely, she has the right to wield her pen for its Suppression. Surely, she may without throwing aside the modest refinements which so much become her sex, use her influence to lead her fellow mortals from the destroyer’s path.”

Throughout its publishing lifetime, The Lily retained its focus on temperance issues (relating horrific stories about drunken men and the untimely ends they often met while intoxicated); however, as Bloomer’s association and admiration of Stanton grew, the paper began to expand with articles about other issues of interest and importance to women. Stanton, writing under the nom de plume “Sunflower,” began by writing about issues such as education, child raising, and temperance; however it was not long until her focus shifted to women’s rights.

The issue of “dress reform” came to the forefront, for all the reasons previously mentioned, and Bloomer took a very active role in promoting practical clothing alternatives to the restrictive Victorian uniform of the day. Bloomer became enamored of a fashion developed by Elizabeth Smith Miller of Geneva, New York. Miller, copying the pantaloons worn by women in Turkey and other eastern cultures, had created a uniquely American take on this exotic dress with a knee-length dress over a pair of ankle-hugging trousers. Though Bloomer denied having anything to do with the development of this fashion, due to her repeated articles and illustrations of the outfit in The Lily, it became known as the Bloomer Costume.

Women’s rights supporters, professional women, and those in occupations that made blousy skirts and dresses a physical hazard quickly adopted the fashion. One woman, a physician named Fedelia Rachel Harris, not only adopted the look, but also publicly derided some of her fellow women who did not.

Dr. Harris was born in Portland, Chautauqua County, New York, on April 19, 1826. While still an infant, she suffered a horrifying burn to her neck that left her in pain and disfigured; however, this injury planted the seed of ambition in Harris. Harris, intrigued in physiology and the workings of the human body, became determined that one day she would become a physician. At the age of 12, she obtained a copy of Coombe’s Physiology, and at age 17, she underwent an extremely painful operation to relieve the pain caused by her disfigurement. For the next three years, she endured even worse pain that only strengthened her resolve to become a physician.

In Cleave’s Biographical Cyclopedia of Homeopathic Physicians and Surgeons, Egbert Cleave wrote, “Accordingly, as she felt reasonable assurance of continued life, she began teaching incessantly in order to provide means to attend a medical college. In 1854, she began a regular course of medical studies under a private preceptor. During the winter of 1855-56, she read and practiced under Dr. O. Davis, formerly Professor of Obstetrics in the New York Central Medical College, but at that time conducting the Eclectic Therapeutic Institute, Attica, N.Y. In 1856, she entered, and, in 1857, graduated from the Eclectic Medical College, Cincinnati.”

Upon graduation, Dr. Harris opened a practice in, of all places, Beaver Dam, Wisconsin and was one our city’s first physicians. It was while she lived in Beaver Dam that she wrote a letter published in Sybil, another women’s newspaper whose mission statement stated, “The Sibyl: A Semi-Monthly Journal of Eight Pages, Devoted to Reforms in Every Department of Life.” In the book, Traveling Economies: American Women’s Travel Writing author Jennifer Bernhardt Steadman writes the following:

“Strategic representations of antireform women pepper the columns of the Sibyl. Frequently, unsympathetic women are rendered as merely backward and powerless. A letter from Miss Fidelia R. Harris, MD, describes the contrast between her own independence and fitness for public life and that of a group of fashionable women gathered at the scene of a fire:

“Among the women who were standing with me on the corner, were hooped ones and hoopless ones, some with skirts held in their hands to an altitude not comporting with popular ideas of decorum, (it was a muddy, sloppy, sleety, night) and some with robes trailing in the mud, in accordance with the most approved and sensitive ideas of gracefulness, (?) and I stood among them, in the proudly dignified consciousness of being clothed in accordance with the dictates of reason and propriety.

“Oh, dear, dear!” said my good neighbor Mrs. B. as she stood with both hands full of cumbersome skirts, “Oh dear, dear! Can’t we do something!” “No,” I replied, “you see there is nothing can be done for the burning building, and there are plenty of men at work for the others.” “Oh, dear, well I wish WE could help!” I involuntarily laughed at the idea. Poor, fettered creature! How could you help, be the necessity ever so great. And yet, that is but the echo of the heart cry that is going up all over our land from thousands of just such fettered women.”

(“Letter from Miss Fidelia R. Harris, MD, Beaver Dam, Wisconsin,” Sibyl, March 15, 1859)

It is plain what our groundbreaking physician thought of the “poor, fettered creature(s)” and their slavish devotion to fashion. What is insightful is that even here “on the western frontier” women adhered to a dress code clearly impractical for the area in which they lived and even failed to forgo wearing it when, if dressed as Dr. Harris, they could have been instrumental in saving a Beaver Dam building or two from a devastating fire.

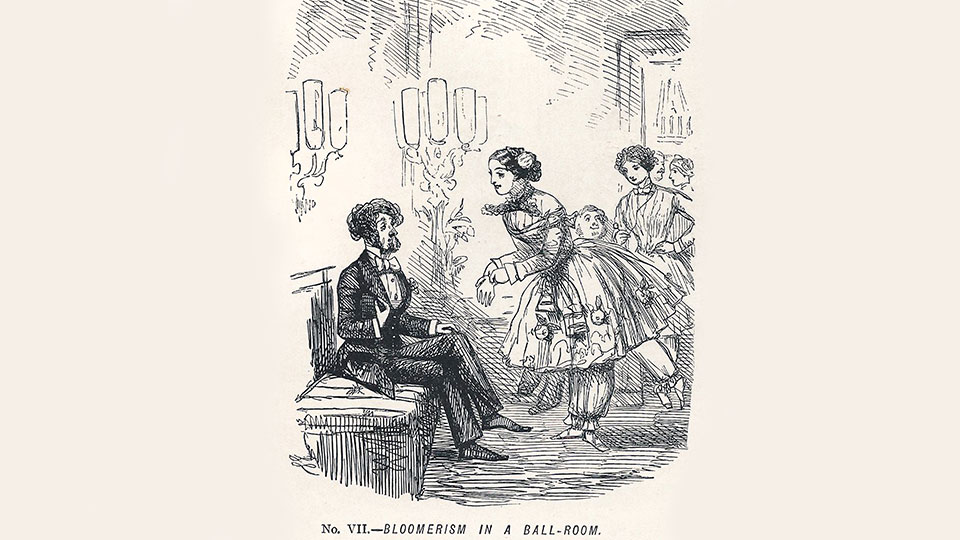

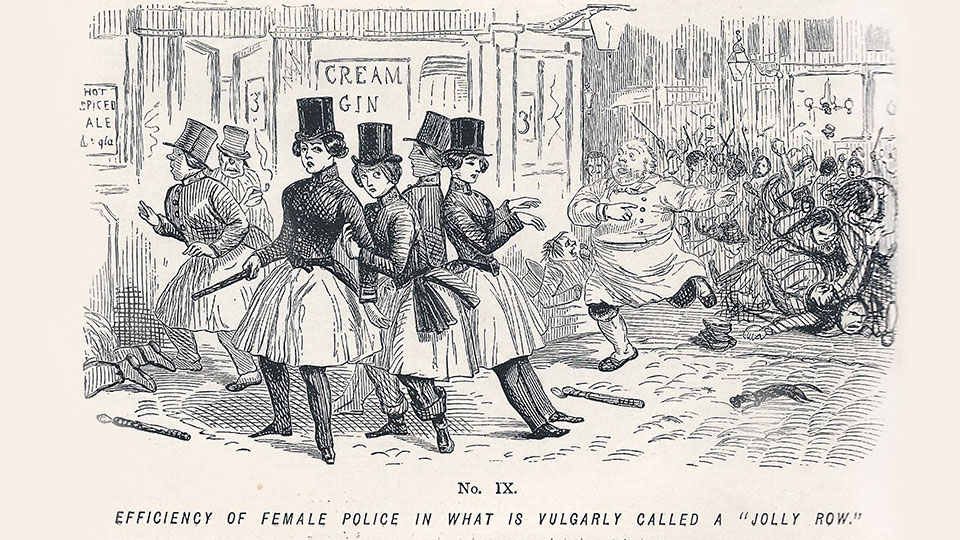

It should come as no surprise that the wearing of bloomers was met with disgust and outrage. Women dressed in this manner found themselves derided in newspapers, in person, and in comics across the US and even across the “pond” where sketch artist John Leech and others published a series of extremely unflattering illustrations in the periodical Punch. In these illustrations, bloomer-clad women are seen smoking, drinking, and taking over traditional male roles with “appropriate” accompanying captions.

Tired of the nearly ceaseless attacks in the press, and with the advent of the much more comfortable bodice and crinoline, even Bloomer herself shelved the pants and wore the new comfortable dress. Fashion reform had reached a “cease fire” with the advent of easily wearable, fashionable dresses; however, the fight for women’s rights, especially suffrage, was only getting started. Women’s suffrage was not to be obtained for another 50 years and the struggle for equal pay for equal work continues to this day.

On a lighter note, bloomers themselves actually did make a popular comeback in the 1890s, when women became enamored with the bicycle. Being mass-produced for the first time, and financially accessible to a large number of Americans, the popularity of bicycle riding prompted women to again adopt the bloomer costume in order to ride without hindrance. Apparently, even in the 19th century, fashion was cyclical.