Excavations Planned At Satterlee Clark House in Horicon

May 19th 2018 – Satterlee Clark House – Horicon, WI – 10:00 am to 4:00 pm

Satterlee Clark and the Winnebago Indians of Horicon and Rock River

In the early history of Dodge County Wisconsin in the area we now call Horicon there were numerous groups of Native American peoples that lived on the Horicon Marsh and the Rock River; and utilized the land and water with its numerous natural resources. Among these groups of people were the Potawatomi, Menomonee, the Sauk and Fox, the Sioux, and most notably, the Winnebago; or as they refer to themselves today as the Ho Chunk Nation of Wisconsin. One of the earliest historical mentions of the Winnebago people in the Horicon area was related by Satterlee Clark in the pages of the History of Dodge County Wisconsin 1880in which Clark describes his layover in Horicon during a portage from Lake Winnebago and its southern outlet the Fond du Lac River to the upper Rock River. At the southern mouth of the Horicon Marsh on the night of September 2, 1830, Clark recollects: “White Breast” (Maunk-Shak-Kah, as the Winnebago pronounced it) was for many years one of the many noted Winnebago villages on the upper Rock River where the city of Horicon now stands.” Clark states: “I slept in an Indian lodge on the east bank of Rock River, where Horicon now stands. There were two rows of lodges (wigwams) extending several rods north from a point near where the Milwaukee & St. Paul Bridge (railroad trestle) now spans the Rock River. The population of White Breast, I should judge, was close to two thousand-bucks, squaws, and papooses. I was on my way in the company of a Winnebago Indian named White Ox to an Indian settlement at the head of Lake Koshkonong. I was but fourteen years of age, and lived with my father at Fort Winnebago. The Indians treated me well, and I have no cause to complain of ill-usage at their hands at any time during the seventeen years thereafter that I traded with them. They always possessed and exhibited the warmest friendship for me, and now, when a few scattered remnants of the once powerful tribe that inhabited Southeastern Wisconsin come to Horicon, they never go away without paying me a visit.”

Today we know this area of Horicon as the area of South Hubbard Street extending north to Mills Street, and west and north to Vine and Elm Streets; stretching to the mouth of the Rock River as it flows south from the Horicon Marsh. It is an area today of residential properties, various businesses, and the John Deere Corporation. James Milton Smith’s painting depicts this area as it may have looked in the 1830’s with the numerous Native American inhabitants.

Chief White Breast was also known to have two other village locations on the Sugar River in Southwesters Wisconsin in 1829 as related in an account by Ely Rasdell. Rasdell states that White Breast’s father Kee-zuhtsh-ga (meaning soft shell turtle) and his grandfather Ma-sho-pa-ka (meaning grizzly bear head) had resided on Lake Koshkonong in the main principle village of the Winnebago on the lower Rock River just south of Horicon; and would also frequent the Horicon area in their travels for seasonal subsistence. By as early as 1825 the Winnebago had fourteen established villages on the entire span of the Rock River.

Satterlee Clark was born in Washington D.C. on March 22, 1816. He attended Utica Academy in New York, and shortly after in 1828 moved to, and settled for a short time at Fort Howard in Green Bay, Wisconsin Territory at the age of twelve with his father. Two years later in 1830 he was appointed Sutler at Fort Winnebago by President Andrew Jackson, but because of his young age was forced to subcontract the work to a resident of Detroit named Oliver Newbury; but non-the less he served as the principle Sutler who’s job as a civilian merchant was to sells provisionsto the United States armyin the field, in camps, or in quarters. Sutler’s sold wares from fort stores, from the back of a wagon, or even from temporary tents while traveling with an army. Satterlee Clark worked from Fort Winnebago from 1830 to 1843; and he came into contact with many different Native American peoples; especially the Winnebago people, who altered his trading practice towards them because of their want for modern European goods. There he also met and married his wife Eliza, the young daughter of a southern military officer stationed at Fort Winnebago. They were married in the Old Indian Agency House.

Fort Winnebago and the Old Indian Agency House was located overlooking the eastern end of the portage between the Foxand Wisconsin Rivers, east of present day Portage, Wisconsin. It was the middle one of three fortifications along the Fox-Wisconsin Waterwaythat also included Fort Howardin Green Bay, and Fort Crawfordin Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin. Fort Winnebago was constructed in 1828 as part of an effort to maintain peace between white settlersand the region’s Native Americantribes following the Winnebago Warof 1827. The fort and the Indian Agency House served directly to deal with the Winnebago Indian presence in this region. Indian Agent John Kinzie was appointed to oversee the Indian Agency House in 1828, and eventually with his wife, Juliette Magill Kinzie, they lived together at the portage from 1832-1834. Juliette Kinzie would later write of the young couple’s experiences at the portage in her book, Wau-Bun, the “Early Day” in the Northwestwhich chronicled their experiences dealing with the Winnebago people in this region in paying out the annual annuities promised by the United States government; this included the Winnebago bands along portions of the Rock River.

The strategic importance of the portageon the Fox-Wisconsin Waterwaywas central to maintaining order in this new territory, and on the heavily traveled connection between the Great Lakesand the Mississippi River. Fort Winnebago’s location near the portage allowed it to regulate transportation between the lakes and the Mississippi. This afforded Satterlee Clark an opportunity to travel throughout this region and come into contact and trade with many Indian peoples. Clark was a vocal proponent of Indian rights, and was even accused of helping the Winnebago to resist the United States treaty proposal in 1836 in which the government wished to strip the Winnebago of all of their lands east of the Mississippi. Governor Henry Dodge of Wisconsin Territory even went as far as to try to strip Satterlee Clark of his license to trade with the Winnebago because his influence among them was so great. The Winnebago Indians at this time were the most influential Native American tribe in Dodge County, and they held prominent positions on the entire length of the Rock River stretching from the rivers beginnings at the Horicon Marsh all the way down into central and Northwestern Illinois. The Horicon Marsh was once even referred to as the great Winnebago Marsh by early European settlers. William Larabee an early Horicon settler is credited with naming Horicon after Lake Horicon in his native New York. (Now called Lake George.) Horicon was thought to mean “clear or pure water” by the local Horicon Indians.

Despite Satterlee Clark’s efforts to persuade the Winnebago from ceding their lands; the Winnebago eventually ceded all their lands in Wisconsin in various treaties beginning in 1829 and again in 1832 in which the region of Horicon and Dodge County was included. A third treaty drafted in 1837 stipulated the removal of the Winnebago to Iowa and increased European settlement immediately followed. Dodge County was created by an act of the Wisconsin Territorial legislature in 1836, and was named in honor of Henry Dodge. Even though many Winnebago Indians were forcibly removed from their ancestral homelands due to questionable treaties many returned to Dodge County and the Horicon area in the 1830’s and remained. Dodge County in the 1830’s was still a mostly wild unsettled territory with many Winnebago Indian villages remaining on the Rock River. On Captain T.J. Cram’s map of Wisconsin Territory dated 1839, “Hochungara” (Ho-Chunk) is listed as being a Winnebago Indian village at Horicon, with an ancient Indian trail leading westward to Beaver Dam. Translations of Hochungara include: “the big fish people”, “the people of the parent speech”, and “the people of the original language.” Current Ho Chunk Nation elders say it means, “The people of the big voice,” or “The people of the sacred language.”

In 1845 Mrs. George Beers of Horicon recollects that the Winnebago Indians living near Horicon wore red blankets to distinguish themselves from the Pottawatomie and Menomonee Indians that also frequented the area. Mrs. Beers relates an account that in the 1840’s Horicon was still a very wild and beautiful place. She describes Horicon as an Indian planting ground where many corn hills could be found scattered about the town. She states many Indian burial mounds were scattered throughout the area; and especially in the area of the old train depot on the eastern side of the river. Mrs. Beers was especially fond of the numerous natural springs found throughout the Horicon area that we now know had a direct correlation for the numerous effigy mounds constructed in the area. Springs are sacred to most Native American Tribes in the Great Lakes region including the Winnebago. This has been confirmed through years of archaeological, as well as ethnological research that has determined that often times ancient burial mound sites were constructed nears springs that were deemed scared to the ancient and more modern Native American inhabitants. One interesting story the highlights this belief by the Winnebago was recorded in the History of Dodge County Wisconsin 1880,stating that Vita Spring in Beaver Dam was held is great esteem by the Native American Inhabitants of this area for centuries for its “healing waters” and rightly named it “healing Spring.” The Winnebago medicine Chief Much-Kaw (as he was known to Beaver Dam residents) in the 1840’s referred to the spring as “much good water.” Much-Kaw claimed to be about 120 years old when he finally died in 1860. He contributed his long life to drinking the spring water out of Vita spring in what is now known as Swan City Park.

A number of Winnebago Indian villages were also chronicled to have existed at various times around the Horicon Marsh by other various settlers of Dodge County. Samuel Thomas reported in 1848 and 1849 that the Winnebago village of “Hobnail” thrived on the edge of the Horicon Marsh near Burnett Township in Section 22 on a small stream flowing into the Horicon Marsh. The village was purported to contain roughly 200 inhabitants, including a few Pottawatomie’s. There was reported to be 20 or more round wigwams and longhouses covered with bark and marsh grass rush matting. The longhouses were partitioned off with matting inside, and the Indians inhabited this location from early spring to the beginning of winter. The native men had percussion lock guns and raised some corn hills, and had dugout canoes. Another Winnebago village called “Scalp Village” was also listed around this same time near the old Zoellner’s Mill, in Chester Township on the north end of the Horicon Marsh. Winnebago Indians occupied many other portions of Dodge County as well. Jacob P. Brower, the first permanent settler of Fox Lake relates a story of encountering Winnebago Indians at Fox Lake in 1838 and coming into contact with the Winnebago Chief Mach-koo-kah, and his subordinate Chief known as the “Dandy” by early settlers because of his magnificent facial paint and feather headdress. They are also known to have inhabited virtually every community in Dodge County; with written accounts appearing in the early histories of Beaver Dam, Waupun, Westford, Oak Grove, Burnett, Chester, Williamstown, Theresa, Hustisford, and Lowell to name a few.

In 1851 Dr. Increase A. Lapham Wisconsin’s preeminent scientist comes to Dodge County to survey ancient Indian effigy mounds in the city of Horicon along the banks of the Rock River. In his landmark publication on Wisconsin’s ancient mound sites entitled Antiquities of Wisconsin as Surveyed and Describe, published in 1855, Lapham states: “The most extended and varied groups of ancient works and most complicated and intricate are at Horicon. Plate 37 of represents the principle groups immediately below the town, but does not include all in the vicinity. They occupy the high banks of the river on both sides. There are about two hundred ordinary round (burial) mounds in the neighborhood and all, with two exceptions, quite small. The two larger ones, on the west side of the river, have an elevation of twelve feet, and are sixty–five feet in diameter at the base. The others are from one to four or five feet high. In several of them we noticed very recent Indian graves, covered with slabs or stakes, in the usual method of Modern Indians.” Plate map 37 in Antiques of Wisconsin as Surveyed and Describedillustrates the diverse Late Woodland Period (A.D. 700 – A.D. 1200) effigy mounds and conical mounds still remaining in the area of Horicon in the vicinity of the old Winnebago Indian village in 1851. Mostly destroyed today by development of the modern city of Horicon, a few of these mounds still exist today on Larabee Street and Valley Street along the Rock River.

The city of Horicon today is built entirely built upon hundreds if not thousands of ancient as well as more historic period Native American burials; and this attests to its long prehistoric occupation as a favorite area for habitation among many Native American cultures over many thousands of years. Today archaeologists refer to these myriad mound building cultures as being part of the Woodland Tradition which stretches from about 800 B.C. until about A.D. 1350. Many of these different mound building cultures inhabited the Horicon Marsh and upper Rock River throughout this time period all bring their different mound building styles and ritualism. Many ethnographic researchers and archaeologists have attributed the construction of Late Woodland Period (A.D. 700 – A.D. 1200) effigy mounds to the early ancestors of the Winnebago in this region. Some decedents of the Winnebago claim them to be direct descendants of the mound builders, thus tying themselves to the landscape of Dodge County for thousands of years. This continues to be a hotly debated subject between various Native American tribes and modern ethnological and archaeological researchers. Winnebago myths, stories, legends, and cosmological beliefs illustrate in their oral traditions a rich and varied account of the Winnebago people; and the development of their clan systems that seemingly tie them directly to effigy mound shape construction. Mounds in the shapes of bears, deer, birds of various types, water panthers, and turtles just to name a few. Many of these effigy mound types are preserved in the Nitschke Mounds County Park just outside of Horicon in Burnett Township on County Highway E, two miles west of Horicon.

One interesting ethnographic account recorded in the early history of Beaver Dam is that of an interview of an old Winnebago Chief named Wiscopawis in 1848 by a Mr. Shafer. Wiscopawis relates to him a story that was told to him as a young boy by his ancestors that the effigy mounds were built many years ago by the Indian peoples inhabiting these lands who professed to be very religious and exhibited their beliefs by holding gatherings and worshipping a deity fashioned by their own hands from bags of animal skins filled with earth from their home camping grounds; stating that sometimes these people came by the thousands from long distances carrying these heavy bags of earth on their backs to participate in ceremonies in which building the effigy mounds were done at an appointed place of meeting. Each participant emptied together their bags of earth into one huge pile where the ceremony consisted in shaping this pile in the form of an animal which at once became the object of their idolatrous worship. Before dispersing it was understood where and when the next meeting would take place.

Interestingly Satterlee Clark in his recollections in the vicinity of White Breast village encampment in his 1830 visit to Horicon does mentions the numerous burials along the banks of the Rock River in Horicon, but doesn’t refer to them as ancient effigy and conical burial mounds; stating “Along the banks of the river could be seen the last resting place of many good Indians.” Clark does relate the practice of the Indians at Horicon burying their dead above the ground along the banks of the Rock River on prepared platform scaffolds constructed of wooden poles and brush about six or seven feet above the ground. Interestingly he also relates how it was a common practice of the Indians to bury the dead in canoes covered with bark and sealed with tamarack gum and then placed up on these platforms. This was a burial practice that was also seen on the lower Rock River in Wisconsin near Lake Koshkonong as related in the memoirs of Aaron Rankin who first came to what is now called Fort Atkinson with the first settler Dwight Foster in 1836. On a deer hunting trip he states: “Coming out near Rock River I saw a canoe suspended by two crotched posts stuck in the ground. I had been told there was a dead Indian in the canoe, and climbing up the posts I looked over into the canoe. Well, all there was left of that Indian was a few bones and a piece of Blanket.”

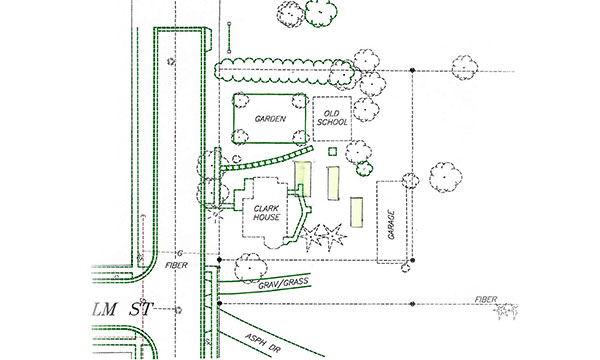

Satterlee Clark eventually moved to Horiconin 1855 and worked for the railroad, but prior to that he had curtailed his Indian trading for a time being and moved for a brief period to Green Lake, Wisconsin (then Marquette County) where he studied law. Clark a Democrat was a state assemblyman from Marquette County in 1849, and later from Dodge County in 1873. He also served as a representative of Dodge County in the State Senate from 1862-1872. Outspoken in his political views he vigorously opposed the Civil War and frequently praised the Confederate leader, Jefferson Davis, whom he had known briefly at fort Winnebago. Although considered a Copperhead, Clark’s warm personality and friendly, accommodating nature made him a popular figure with both whites and Native Americans. Once in Horicon Clark used his popularity with the Native Americans to resume his trade with them. He established a trading post out of the upper back attic window above the original kitchen of his home in Horicon located on 322 Winter Street. Local Horicon lore has it that Clark was willing to trade with the Indians one at a time by making them climb a narrow stairs to a small platform on the upper back side of the original homestead house. Once their Clark would open a trap door window from the storage attic and conduct trading business with the Indians through this small window. Clark wanted to make sure the Indians did not take advantage of him and ransack his trading supplies storage. This system was a way to control the access to the goods. This home was built on a hill on the east side of the Rock River overlooking the strategic beginnings of the river flowing south out of the mouth of the Horicon Marsh. This house today is owned by John Deere Corporation is known as the Satterlee Clark Historic House and is the home of the Horicon Historical Society. This location was a strategic location for control of the upper Rock River and access to the Horicon Marsh for thousands of years. In his recollections Clark describes the many wigwams and Indian encampments scattered along the Rock River near his home and trading post at the mouth of the Horicon Marsh. “Hunting, fishing, and trading were the chief pursuits of the males. The Squaws devoted their attention during the spring and summer months to raising corn; and the autumns and winters to dressing deer hides, making moccasins and building fires in their wigwams. During the warmer weather they lived in wigwam lodges built of white cedar bark. Within these lodges they were constructed of poles, and grass mats with very comfortable berths, where the weary huntsman stretched himself in sleep at night. In the winter, wigwams were substituted for these airy lodges. These wigwams were made of heavy mats prepared from the grass which grew upon the marsh and the borders of area lakes. A strip of matting, two or three feet wide, would be stretched around the bottom of a series of poles placed in the ground certain distances apart, coming together at the top eight or ten feet from their base. An embankment of snow or earth, (if the former did not exist in sufficient abundance), was then thrown up about the outside of the matting: another and another strip of these same grass materials being placed above the first until the circular wall became of sufficient height to protect the inmates from the chilling blasts of wind, which howled through the forest, the top of the wigwam being left open to allow smoke to escape from the fires, around which the Indians gathered at night to relate their deeds of war or tell stories of love. When the drowsy God of sleep asserted himself, they would wrap themselves in their blankets, turn their feet to the fire and obey his commands. Their bed was the cold, solid earth, their sheets, simple grass mates. The couch was not downy, but it was comfortable.”

References:

History of Dodge County 1880

Horicon Reporter March 6, 1914 “Stories of Early Days in Dodge County”

The Wisconsin Archeologist. Volume 2 No. 3 1923

The Wisconsin Archeologist. Volume 17 No 3. 1905

Archives of the Horicon Historical Society. Horicon IndiansAccession No. L11-129-13

Madison Democrat, Sept. 21, 1881; Colls. State Historical Society. Wis, 8 (1879), 9 (1882) WPA Field Notes.

The Portage Democrat. March 28, 1879. Pierre Paquette & The Early History of Fort Winnebago as Narrated by Hon. Satterlee Clark at the Court House in Portage, on Friday Eve, March 21, 1879.

Lore.Volume 27 No. 2, Summer 1977. Milwaukee Public Museum Library Dec. 13, 1977

Cultural Resource Study of the Overlook and Parking Lot, Horicon National Wildlife Refuge, Dodge County, Wisconsin.Report of Investigations No. 677. Great Lake Archaeological Research Center. November 2007.